FALSE

Improving animal welfare doesn't have to be a burden for breeders, and human welfare and animal welfare are closely linked. However, depending on the situation and the improvements needed, they can be a burden for the breeder, who should not have to bear it alone.

Keep in mind

- Some improvements can be costly for breeders

- The majority of animal welfare improvements can be achieved through day-to-day actions that do not require major investments or changes in practices

- Improving animal welfare is good for the breeder's welfare: it's an opportunity, not a constraint!

It’s an established fact that taking into account and improving animal welfare on farms (but also at home, in animal experimentation…) is an important expectation of society!

These improvements can, depending on the case, be implemented through changes in practices or in the animals’ environment. Some of these improvements require little effort, while others require a thorough overhaul of certain practices or major investments. In these cases, the constraints on breeders will not be the same.

What’s more, certain improvements, once implemented, can be a source of satisfaction and contribute to the breeders’ welfare, in line with the “one welfare” principle.

In addition to analyzing the literature, we interviewed three pig breeders (Adrien, Eric, and Frédéric) who have been experimenting with group sow housing. Some of their comments are reported here.

Animal welfare improvement and financial constraints

Improving animal welfare on livestock farms can sometimes require major investments. This is the case, for example, of modifications to livestock buildings imposed by regulatory changes in recent years.

Major investments in building modifications

European Directive 2001/88/EC, transposed into French law by the Order of January 16, 2003, has made it mandatory since January 1, 2013 for pregnant sows to be housed in groups (at least for the period between 4 weeks after service and 7 days before farrowing), whereas previously they were confined to individual stalls.

This evolution, based on improved scientific knowledge of sows’ behavioral needs[1] (more space, greater freedom of movement, better expression of social behavior) has called for upgrades in breeding housing, either through renovation or the construction of new buildings. These modifications involve an important cost and workload for breeders.

Renovating my building (78 stalls for pregnant sows) cost me around €35,000, and on top of that I had to hire an extra employee for three weeks to help me dismantle and reassemble everything

ADRIEN, PIG BREEDER

In the poultry industry, the decree of February 5, 2022 concerning the ban on the culling of chicks of the Gallus gallus species in the egg industry has required hatcheries to equip themselves with equipment to determine in ovo (i.e. in the egg) the sex of the embryo in order to destroy it before hatching (see our decoding article on the decree). This regulatory change prevents the killing of millions of male chicks every year, but has needed significant investment (several tens of millions of euros) in new equipment.

In some cases, government subsidies or other mechanisms have been put in place to reduce the financial burden on the sector or on breeders themselves. For example, in the case of in ovo sexing, the French government, through FranceAgriMer, financed part of the equipment in hatcheries to the tune of 10.5 million euros. At the same time, an inter-professional contribution has been set up to share the costs incurred by hatcheries with retailers[2].

To bring pig farms up to group housing standards, the government introduced a subsidy, under conditions, which was set at 20% of eligible investments up to a limit of 15,000 euros per farm[3].

I received a €5,000 grant to bring my building into line with the new directive.

ADRIEN, PIG BREEDER

Despite this, part of the investment often remains at the breeder’s expense, and certain developments linked to animal welfare represent an economic constraint that must be compensated for.

Investments over time

Other investments are necessary as part of a continuous improvement approach. Like carpets to ensure better lying comfort for dairy cows in cubicles, interactive materials to enrich living conditions for pigs, enrichment systems installed in poultry buildings… All these investments, which promote animal welfare, have a cost for breeders and represent a financial constraint.

But improving animal welfare doesn’t just mean upgrading buildings… it can also mean changing farming practices.

Improving animal welfare through profound changes in farming practices

Changes in practices can also be a source of constraint for breeders, either when they require major modifications or when existing alternatives are difficult to implement.

First and foremost, these changes may encounter a degree of “resistance to change“. Educational methods and a good explanation of the objectives and procedures can help breeders to better understand the benefits of investing in these changes to improve animal welfare.

I started in 2007 (farrow-to-finish, 300 sows). I was very reluctant and angry at the administration, which was forcing us to group our sows by 01/2014 at the latest! Aside from the financial aspect, technically, I was afraid of abortions, poor leg conformations and infection resulting from fights during grouping. Fortunately, I worked with my vet beforehand to create homogeneous groups (sows of the same age, for example) and to my great surprise, after the first 2-3 days of grouping, the animals were very calm.

ERIC, PIG BREEDER

Grouping was complicated at first. I would say for almost 1 year, the time it took for the sows to get used to each other.

FREDERIC, PIG BREEDER

Even after an adaptation period, some changes can still be restrictive for breeders.

Let’s take the example of the ban on live castration in piglets, which came into force on January 1, 2022 following the decree of February 24, 2020 (see our Decoding article on the decree). There are several alternatives to this practice: keeping entire male pigs, immunocastration or surgical castration with the use of a local analgesic and anesthetic treatment. By way of derogation, this surgical castration may be carried out by breeders, provided they have taken the regulatory training course designed by the IFIP (French Pig Institute)[4].

The use of anesthesia and analgesia eliminates pain during castration, and is therefore beneficial to piglet welfare. It does, however, require a change in breeders’ practices. Previously, piglets needed to be handled only once for the castration itself, but now two manipulations are required, one for anesthesia and analgesia, then one for castration after a 15-minute wait for the product to take effect. This evolution therefore requires more time, more manipulations, a different organization which can be perceived as a constraint by breeders…

However, and this is important to emphasize, the majority of improvements in animal welfare can also be achieved through day-to-day actions, or simply better observation of animals, which do not require major investment or upheaval in practices.

Improving animal welfare along the way

A better human-animal relationship

One of the best ways of improving animal welfare is to improve human-animal relationships. There are many human interventions in animal husbandry, and their perception by the animal has a major influence on its welfare. Implementing practices in a positive, respectful human-animal relationship is an essential way to reduce stressful situations for the animal during these interventions, whether they require human contact or only the presence of humans[5]. And yet, in many cases, improving human-animal relations does not require excessive investment or changes in practices on the part of the breeder.

In fact, the human-animal relationship is built up gradually, as the various interactions take place. It’s the balance between positive and negative interactions that determines the state of the relationship. The breeder – as all humans working with animals – must therefore encourage positive contact (calm movements, gentle touch, calm voice, etc.). Animal habituation, especially at certain sensitive periods in their lives, is also a good thing. To find out more about the human-animal relationship, please visit our dedicated page.

Improvement through animal observation

Another relatively easy avenue for improvement is to take the time to observe the animals and their behaviors, to recognize their emotions in order to be able to better identify their needs, spot possible disorders earlier and ultimately improve their welfare. Similarly, gaining a better understanding of their sensory perceptions and reactions can help to approach the animals, thus fostering the establishment of a positive human-animal relationship.

In brief

Depending on the situation and preferred approach, improving animal welfare on the farm can be more or less demanding. Improvement based on increased daily attention is not too restrictive, whereas improvement requiring a modification of the building or certain practices can quickly become difficult to implement. Fortunately, many animal welfare improvements are also beneficial to the breeder's welfare, and this benefit tilts the balance in a positive direction.

Improving animal welfare is often beneficial to the breeder's welfare

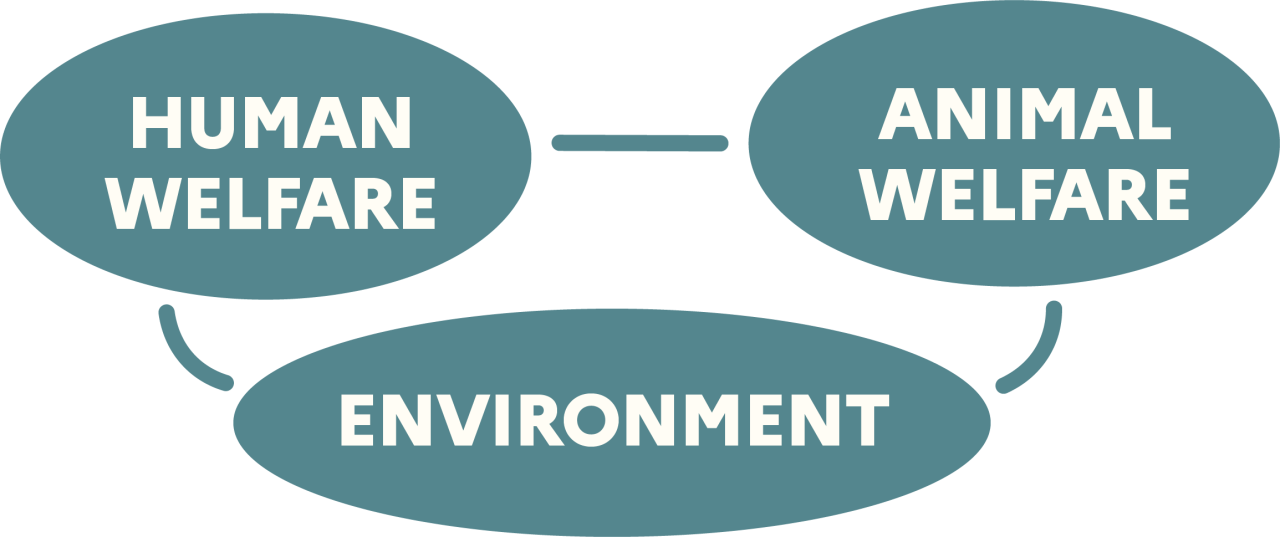

Improving animal welfare is often also a source of improved welfare for breeders. This principle is stated in the “One Welfare” concept, which means that animal welfare, human welfare and environmental protection are closely linked.

Improving animal welfare can influence human welfare through easier animal handling, thus limiting stress and the risk of accidents, but also indirectly by improving animal productivity and reducing, for instance, disease-related costs, thereby increasing breeder income Finally, it has been shown that a high level of animal welfare is often a source of satisfaction for breeders.

Improved handling

A good human-animal relationship, fostered by good socialization but also by a good knowledge of the animals and their own perception, contributes to the welfare of animals but also of breeders[6]. Indeed, animals with less fear of humans are easier to approach, calmer during moving or handling, whereas certain tasks are more difficult and dangerous when faced with an animal that seeks to avoid human contact[7]. However, animals with a very low level of fear of humans can sometimes be more difficult to handle[8]. The importance of a good human-animal relationship also applies to transport to the slaughterhouse. Negative interactions during loading or unloading can affect meat quality[9].

A good human-animal relationship is therefore particularly important and beneficial for the breeder, especially as contact and interaction are particularly frequent on the farm.

Beforegroup housing, the sows rarely saw me walking by, as the corridor was behind them. So they couldn’t see me. Now, they see me a lot more, interact with me more… so they’re much better socialized, which makes handling easier and reduces my workload..

ADRIEN, PIG BREEDER

Impact on production and animal health

Improving animal welfare also often contributes to increased farm profitability, whether through improved animal performance or lower costs.

The most obvious link between welfare and productivity is reduced mortality. Conditions that improve animal survival increase the breeder’s sales volumes. This is the case, for example, with neonatal mortality (lambs, piglets, calves, etc.), which can be reduced by better housing conditions, better disease management or careful colostrum distribution. In fact, the animal’s health can deteriorate as a result of stress, which reduces its immune response and increases its vulnerability to disease[10]. The breeder then has to call in his veterinarian, pay for treatment and spend time with the animals that need care, which, in addition to lowering performance, can represent considerable costs. Welfare improvements can limit these negative impacts, and it has been shown, for example, that adding straw is both economically profitable and contributes to cattle welfare[11].

Since switching to group housing, I find that my animals are healthier.

ADRIEN, PIG BREEDER

Numerous studies have shown that improving animal welfare is also a factor in improving animal performance. For example, it has been shown that reproductive performance in sows[12] and milk production in dairy cows are improved by a good human-animal relationship[13]. Similarly, improved comfort in dairy cows improves productivity and longevity[14]. The results of this study also highlighted the fact that, to maximize financial benefits, welfare must guide all aspects of housing. Finally, it was shown that lambs reared in a comfortable, enriched environment had better growth, heavier carcasses and better conformation than lambs reared in a non-enriched environment[15].

I think that grouping sows has improved productivity quantitatively, with more “tonic” farrowing in particular»

ADRIEN, PIG BREEDER

Impact on breeder satisfaction and working conditions

I felt more like a breeder. I understood that we could have a good relationship with the sows.

ADRIEN, PIG BREEDER

In the end, our working conditions improved, so did the living conditions of our animals. Taking the time to think carefully about our project enabled us to make the most of a forced investment! We never looked back.

ERIC, PIG BREEDER

In practical terms, I no longer have to clean up after each sow every morning, and I estimate that I save 35 minutes a day.

ERIC, PIG BREEDER

Impact on sales price

Last but not least, improved animal welfare can be promoted commercially via certain labels or voluntary initiatives, such as the animal welfare label developed for broiler chickens.

In short

- In many cases, improving animal welfare is good for the breeder’s welfare, and should be seen as an opportunity rather than a constraint. This is particularly the case when improvements are made on a day-to-day basis through improved practices and better observation of the animals.

- However, some welfare improvements can be costly for breeders, requiring significant investment. Similarly, some improvements can lead to a reduction in the breeder’s income. Reducing stocking density and increasing the space available per animal can be costly for the breeder, who raises fewer animals in the same given space, but finds other rewards (improved productivity for each animal, better selling price, improved quality of work, etc.).

- It seems important to provide support and assistance processes when implementing these animal welfare improvements for livestock breeders, who should not have to bear the additional costs alone. This could take the form of government subsidies, reduced retailer margins, or consumer acceptance of slightly higher prices for animal products.

- Finally, it is important to bear in mind that it’s not always easy to link improvements in welfare to financial benefits, and that many other benefits (workload, satisfaction, ease of handling, etc.) are associated and must therefore be taken into account in the cost/benefit balance.

Additional information

Tallet C., Courboulay V., Devillers N., Meunier-salaün M.-C., Prunier A., Villain A. (2020). Mieux connaître le comportement du porc pour une bonne relation avec les humains en élevage. INRAE Productions Animales, 33(2), 81–94. https://doi.org/10.20870/productions-animales.2020.33.2.4474

[1] EFSA, 2007. Animal health and welfare aspects of different housing and husbandry systems for adult breeding boars, pregnant, farrowing sows and unweaned piglets. EFSA Journal 5(10), https://doi.org/10.2903/j.efsa.2007.572

[2] https://www.lafranceagricole.fr/actualites/article/806640/une-cotisation-interprofessionnelle-pour-les-surcouts-de-l-ovosexage

[3] Note of February 6, 2008 : https://info.agriculture.gouv.fr/gedei/site/bo-agri/instruction-N2008-4006. The subsidy was increased in mountain areas and for young farmers.

[4] https://ifip.asso.fr/centre-de-ressources-castrabea/

[5] Improving animal-human interactions through better relational practices. Fascicule « Améliorer le bien-être animal » Editions Quae https://www.quae-open.com/produit/184/9782759234615/le-bien-etre-des-animaux-d-elevage

[6] Tallet C., Courboulay V., Devillers N., Meunier-Salaün M.-C., Prunier A., Villain A., 2020. Mieux connaître le comportement du porc pour une bonne relation avec les humains en élevage. INRAE Productions Animales 33(2), 81–94. https://doi.org/10.20870/productions-animales.2020.33.2.4474

[7] Hemsworth P., 2000. Behavioural principles of pig handling. In: Grandin T. (Eds), Livestock handling and transport, 2nd edition, 255-274. CAB International, Oxon, Wallington, UK.

Rault J.-L., Waiblinger S., Boivin X., Hemsworth P., 2020. The Power of a Positive Human–Animal Relationship for Animal Welfare. Frontiers in Veterinary Science 7, https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2020.590867

[8] Breuer K., Hemsworth P. H., Coleman G. J., 2003. The effect of positive or negative handling on the behavioural and physiological responses of nonlactating heifers. Applied Animal Behaviour Science 84 (1), https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-1591(03)00146-1

[9] Terlouw C., Cassar-Malek I., Picard B., Bourguet C., Deiss V., et al., 2015. Stress en élevage et à l’abattage : impacts sur les qualités des viandes. Productions Animales 28(2), 169-182. https://doi.org/10.20870/productions-animales.2015.28.2.3023

[10] Elodie Merlot, 2004. Conséquences du stress sur la fonction immunitaire chez les animaux d’élevage. Productions Animales 17(4), 255-264, https://hal.inrae.fr/hal-02682983v1

[11] Bruijnis M.R.N., Hogeveen H., Stassen E.N., 2013. Measures to improve dairy cow foot health: consequences for farmer income and dairy cow welfare. Animal 7(1), 167–175, https://doi.org/10.1017/S1751731112001383

[12] Courboulay V., Barbier B., Bellec T., et al., 2022. RHAPORC – Améliorer la relation homme animal en élevage porcin au bénéfice de l’homme et de ses animaux. Innovations Agronomiques 85, 323-334, https://doi.org/10.17180/ciag-2022-vol85-art25

[13] Waiblinger S., Menke C., Coleman G., 2002. The relationship between attitudes, personal characteristics and behavior of stockpeople and subsequent behavior and production of dairy cows. Applied Animal Behaviour Science 79 (3),195-219, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-1591(02)00155-7

[14] Villettaz Robichaud M., Rushen J., de Passillé A.M., Vasseur E., Orsel K., Pellerin D., 2019.

Associations between on-farm animal welfare indicators and productivity and profitability on Canadian dairies: I. On freestall farms. Journal of Dairy Science 102(5), https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2018-14817

[15] Aguayo-Ulloa L.A., Miranda-de la Lama G.C., Pascual-Alsonso M., Olleta J.L., Villarroel M., Sanudo C., Maria G.A., 2014. Effect of enriched housing on welfare, production performance and meat quality in finishing lambs: the use of feeder ramps. Meat Science 97 (1), 42–48, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.meatsci.2014.01.001

[16] Hemsworth P.H., Barnett J., Coleman G., 2009. The integration of human-animal relations into animal welfare monitoring schemes. Animal Welfare 18(4), 335–345, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0962728600000737

Hemsworth P.H., Coleman G.J., 2011. Human livestock: the stockperson and the productivity and welfare of intensively farmed animals, 2nd edition. CABI, Wallingford.

[17] Gunnar Hansen B., Østerås O., 2019. Farmer welfare and animal welfare- Exploring the relationship between farmer’s occupational well-being and stress, farm expansion and animal welfare.

Preventive Veterinary Medicine 170, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prevetmed.2019.104741

Keep in mind

- Some improvements can be costly for breeders

- The majority of animal welfare improvements can be achieved through day-to-day actions that do not require major investments or changes in practices

- Improving animal welfare is good for the breeder's welfare: it's an opportunity, not a constraint!

In the end, our working conditions improved, so did the living conditions of our animals. Taking the time to think carefully about our project enabled us to make the most of a forced investment! We never looked back.

ERIC, PIG BREEDER