FALSE

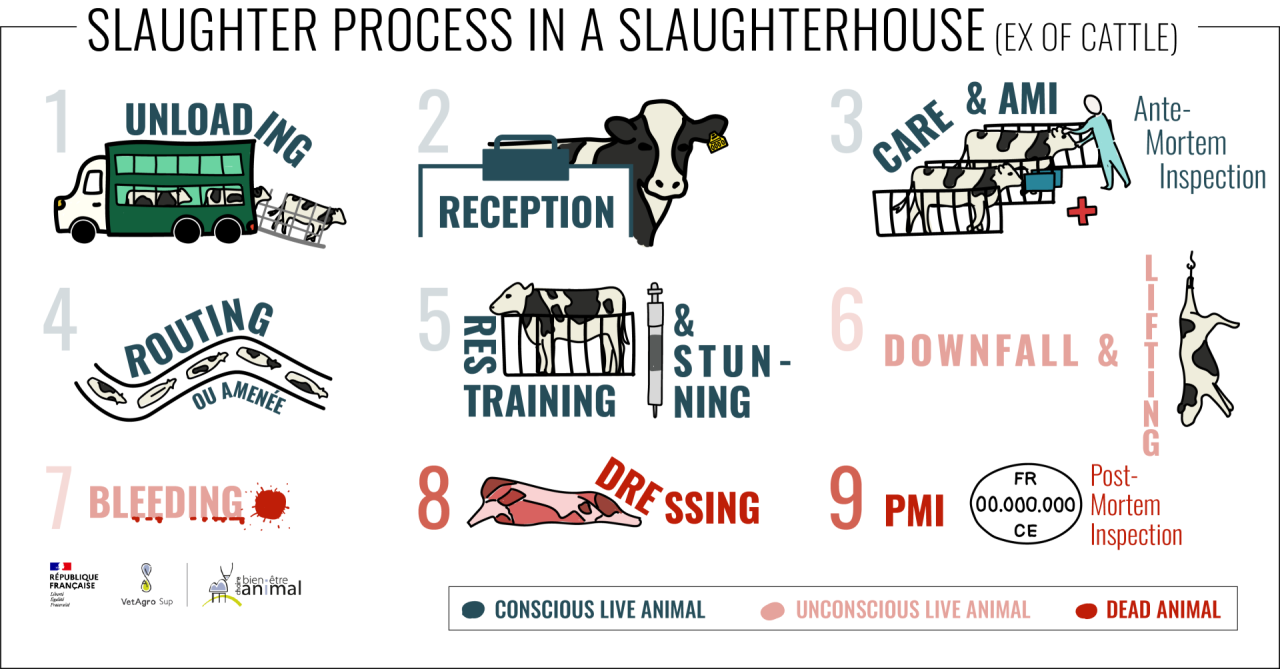

Initially focused on the notion of food hygiene, the laws governing slaughterhouse operations have gradually incorporated the issue of animal protection throughout the slaughter process. Improving this protection relies on staff training and changes in practices.

Keep in mind

- In France, animals are protected, including in slaughterhouses

- In French slaughterhouses, "animal protection" is the relevant terminology, not "welfare".

- Regulations call for appropriate equipment, trained personnel, daily checks and increased penalties in the event of violations

The creation of slaughterhouses in the 19th century and their industrialization have gradually distanced citizens from the reality of animal slaughtering Nowadays, the vast majority of consumers are unaware of the conditions under which the animals they eat are being slaughtered. They are also unaware of the regulations governing slaughter, particularly those concerning animal protection[1].

Did you know?

"Animal protection" refers to standards designed to prevent animal suffering and abuse. In the slaughterhouse, where animals are put to death, this term is preferred to "animal welfare", which expresses a sustainable state involving a positive mental state.

Moreover, cases of mistreatment reported by the media following investigations carried out by abolitionist associations are often the only information available to the public, fuelling both mistrust and disconnection from the reality of slaughter conditions.

What are the existing regulations protecting animals in slaughterhouses? How are they being enforced? The Chaire bien-être animal team explains it all in this article!

Let’s start with a brief history of slaughterhouses. Next, we’ll have a look at how regulations govern all stages of animal slaughter. Finally, we’ll see how government services monitor compliance with these regulations and ensure animal protection in slaughterhouses.

The history of slaughterhouses in France

In France, Napoleon I’s imperial decree of February 9, 1810, instituted the first abattoirs, which opened in 1818, right in the heart of Paris. The concentration in a single location of what were known at the time as “tueries individuelles” (“individual killing places”) serves both a sanitary and a moral purpose.

The former aims to improve meat safety control and reduce the nuisance caused by waste disposal. The latter is designed to protect the public from the spectacle of animals being killed for human consumption. Until then, livestock was killed by the butchers themselves, in spaces adjoining their stalls and opening onto the street. These ” tueries individuelles” served both as annexes to the meat cutting plant and as sewers. However, according to some historians and philosophers such as Montaigne and Kant, acts of violence perpetrated against animals lead to increased levels of violence between humans themselves[2].

Due to resistance on the butchers’ part, the development of slaughterhouses was slow in France. In 1938, more than a century after their creation, there were just about 1,781 abattoirs in France, while some 30,000 “tueries individuelles” still existed. The 1941 ban on these places brought the number of abattoirs to 3,327 by 1948 [3].

📌 Please note

In 2021, France only counted 240 slaughterhouses producing 3.7 million tons of meat (dressed weight) per year (in order of importance: pigs, cattle, sheep and goats, horses)[4]. There are also over 600 registered poultry and rabbit slaughterhouses, of which only about one hundred have significant activity (over 500 tons per year), according to FranceAgriMer[5]. In 2021, they produced 1.1 million tons of poultry[6].

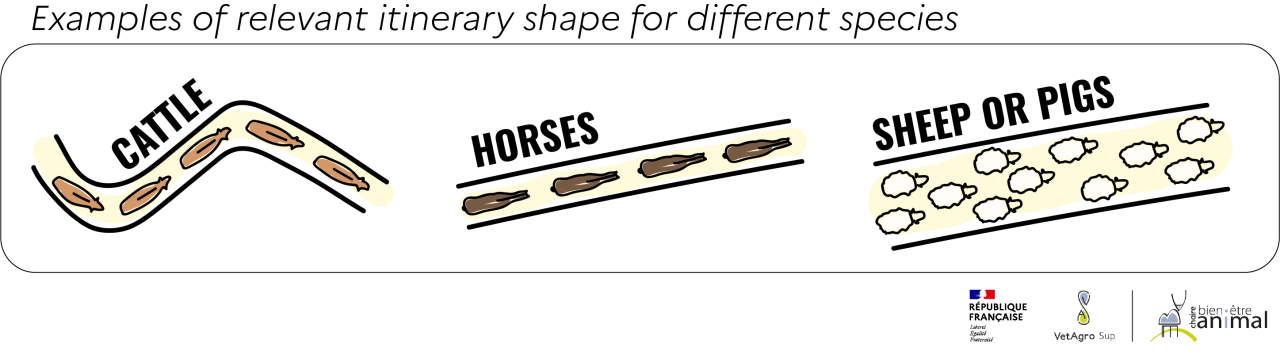

In the 1980s, taking into account the animal’s point of view led to considerable changes in infrastructure, particularly in the United States A pioneer in this field, Temple Grandin, a professor in the Department of Animal Sciences at the University of Colorado, used the fact that cattle naturally move in groups along curves to design wide, curved circuits for slaughterhouses, facilitating the movement of cattle without constraint : animal protection is improved and slaughterhouse performance is enhanced.

Developments in ethology and the growing pressure exerted by society have led slaughterhouses – which were initially designed to protect human sensitivity – to make animal sensitivity a priority as well.

Slaughterhouse operators' animal protection obligations

After presenting the general rules that apply to slaughterhouse operations in the European Union, we’ll take a closer look at the issue of stunning prior to bleeding and the training of slaughterhouse personnel.

European regulatory framework [7]

At the EU level, Regulation (EC) N°1099/2009 is the framework for the protection of farm animals at the time of killing. It is based on the following basic principle: “animals must be spared avoidable pain, distress or suffering at every stage of the killing process“.

Did you know?

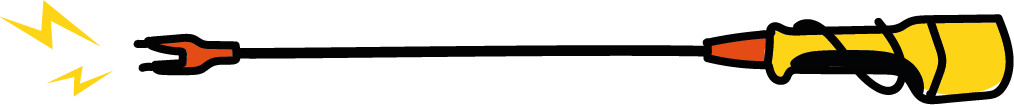

According to regulation (EC) N°1099/2009, the use of instruments which administer electric shocks, commonly known as electroshocking, is to be avoided whenever possible. These can only be used to stimulate adult cattle and pigs that refuse to move when they have room to do so. The animals subjected to them must not show any particular weakness. Shocks may only be applied to the muscles of the hindquarters, must not last longer than 1 second, and must be suitably spaced. Finally, they must not be repeated if the animal does not react [13].

Pre-bleeding stunning management

Stunning prior to bleeding is required by law. This aims to render the animal unconscious, i.e. insensitive to stimuli from its environment or body. As animals of the species in question are capable of both positive and negative emotions, unconsciousness prevents them from experiencing pain and fear during the killing process.[14].

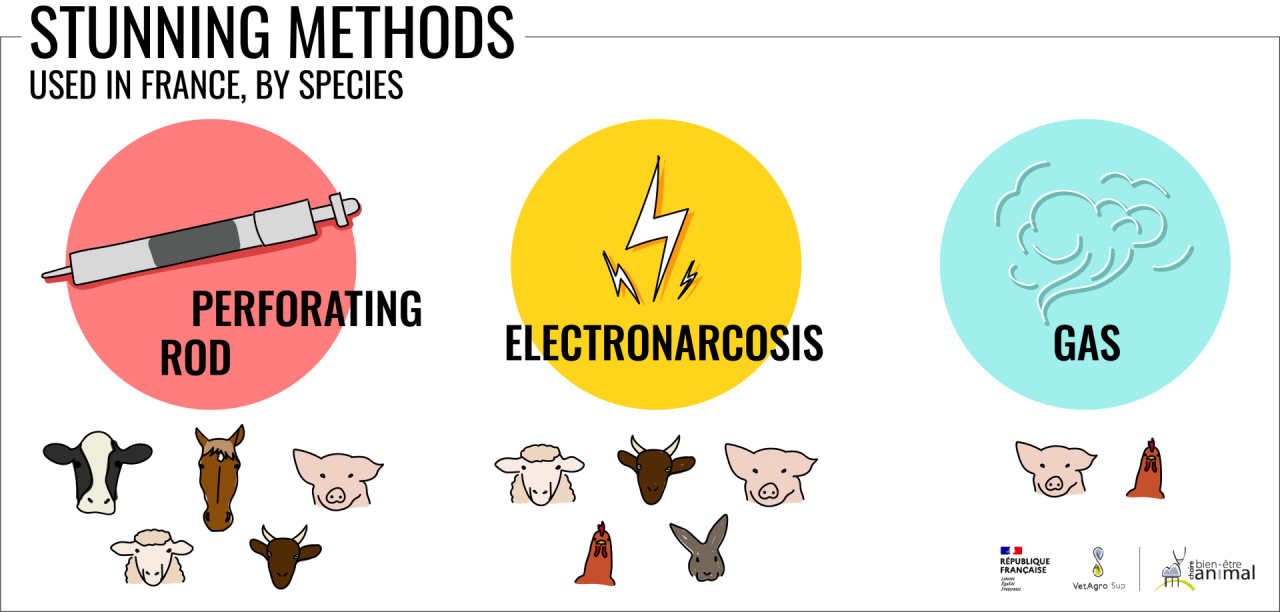

There are three main methods of stunning used in slaughterhouses: mechanical, electrical and gas stunning.

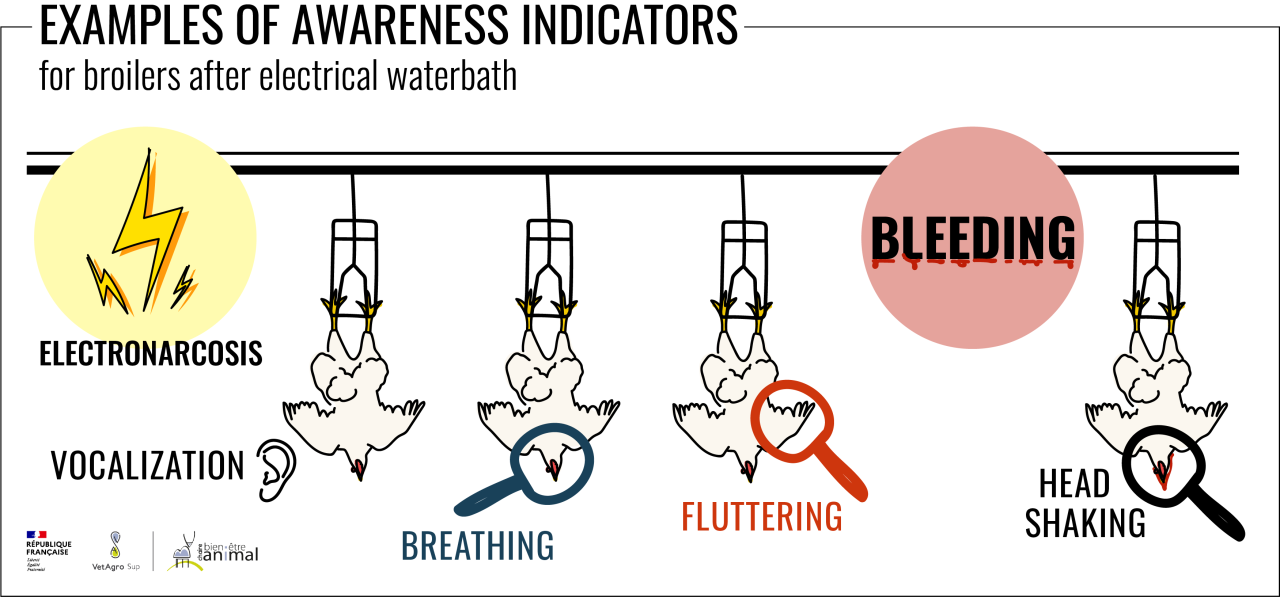

It should be noted that certain behavioral manifestations, while visually impressive, do not necessarily reflect a state of consciousness on the part of the animal: this is the case, for example, with non-oriented reflex movements of the limbs and head in cattle.

In any case, doubt must benefit the animal: the presence of a single sign suggestive of a risk of consciousness must lead to a second immediate stunning.

In addition to permanent and systematic control, additional random control – supervised by the Animal Protection Officer (APO) – is carried out through sampling.

📌 What about slaughter without stunning?

Certain religious slaughtering practices, notably those of Jews and Muslims, are incompatible with stunning prior to bleeding. In these cases, animals can be slaughtered without having been rendered unconscious beforehand.

Although there is no official position from religious authorities on this subject, post-slaughter stunning, known as “relief”, is sometimes practiced to limit the animal’s suffering.

In France, ritual slaughter must take place in slaughterhouses.[17]. These must comply with the following requirements: [18] :

- Have an authorization issued by the departmental prefect;

- Personnel must be trained in the specificities of slaughter without stunning (see part III);

- Have commercial orders for ritual slaughter requiring the use of this derogation and proving the number of animals concerned;

- Ritual slaughter must be done by licensed personnel authorized by approved religious bodies.

Operator training

The way animals are handled has a major impact on their protection. According to the EFSA, (European Food Safety Authority), the main threats to animal protection are directly linked to a lack of staff skills or training, resulting in inappropriate handling and poorly designed facilities.[19].

To guarantee a minimum level of training for slaughterhouse operators, regulation (EC) N°1099/2009 requires them to hold a Certificate of Competence relevant to the operations they perform: handling and care of animals, or killing with or without prior stunning (in French, CCPA or Certificat de Compétence “Protection des Animaux dans le cadre de leur mise à mort”). The APO must hold a Certificate of Competence for all categories of activity in the facility in which he or she is employed.

Regardless of the considered certificate, the training program focuses on three areas:[20]

- Animal knowledge (behavior, physiology, consciousness, sensitivity) and the fundamental principles determining favorable interaction between operator and animal in common practice,

- Knowledge of regulations determining conduct in everyday situations,

- Technical gesture knowledge.

Training lasts a minimum of 7 hours for operators and 14 hours for APOs, with an additional day of training specific to APO missions. Upon successful completion of the individual end-of-training assessment, the issued certificate of competence is valid for 5 years.

📌 What you need to know!

In 2022, all categories considered, there were 29,982 candidates for the CCPA: 29,762 passed the assessment, i.e. 99.27%[21].

Only certain training organizations can provide CCPA preparation training. They must be accredited by the French Ministry of Agriculture and Food Sovereignty, following a rigorous analysis of the offered training.[22]. This accreditation is valid for 5 years.

The list of organizations authorized to provide CCPA training can be consulted here. It is updated regularly.

Official control of animal protection in slaughterhouses

After explaining the role of veterinary inspection services within slaughterhouses, we’ll look at how inspection has been impacted by media coverage of recent cases of animal mistreatment in slaughterhouses.

Operator training

Slaughterhouses’ production activity is subjected to the official inspection service’s permanent presence in the facility: this model is a French exception. Each facility must therefore house a veterinary inspection service (SVI), made up of one or more official veterinarians backed up by official auxiliaries. These state agents are part of the services of the Directions Départementales de la Protection des Populations (DDPP).

The only exception is poultry and rabbit slaughterhouses, where the inspection system was reformed in 2012[23] therefore authorizing slaughterhouse staff to take part in inspections. Previously trained for this purpose by bodies authorized by the Ministry of Agriculture, staff are placed under the control and responsibility of the SVI who, even if not present on a permanent basis, assess their work regularly.

To ensure compliance with animal protection regulations, the SVI carries out three different types of inspections: systematic, regular and annual[24].

Each animal is subjected to a mandatory ante-mortem inspection (AMI) before slaughter by the SVI.[25]. For rabbits and poultry, inspection may not be carried out on all animals, but may be limited to a representative sample from each breeding site. This inspection must be carried out within 24 hours of the animals’ arrival at the slaughterhouse, and less than 24 hours before slaughter.

This stage enables to identify any animal that should be excluded from human consumption, and to prioritize slaughter: a stressed animal with dangerous behavior, or an animal showing signs of weakness following transport, will be given priority for slaughter. It is also an opportunity to detect any violations that may have been committed, during the animal’s breeding or transport to the slaughterhouse.

SVI presence at stunning and killing stations is not permanent. The various stations in the slaughterhouse are inspected regularly and without notice throughout the year. The number and frequency of these inspections depend on the guidelines laid down at the beginning of the year by the Ministry of Agriculture, and on the results of previous inspections.

At least once a year, the veterinary inspection service schedules a full animal protection inspection of the slaughterhouse. On this occasion, all slaughter lines, all species and categories of animals slaughtered, and all slaughter methods are inspected.

📌 What you need to know!

In 2019, 1,500 inspectors carried out official checks in French slaughterhouses[26].

Despite this solid regulatory foundation, there are sometimes abuses in certain establishments, regularly highlighted by animal protection associations. In March 2016, association L214 released images of mistreatment and even acts of cruelty perpetrated against animals in several French slaughterhouses. However, some images that the public may find shocking do not necessarily indicate non-compliance: for example, animals on the bleeding rail showing reflex movements despite being in a state of deep unconsciousness.

However, the publication of these videos has led to a number of actions on the part of public authorities, listed below.

Did you know?

For a carcass to be stamped as fit for consumption, it must have:

- A favorable AMI state (animal correctly identified, clean and healthy);

- A favorable PMI state (carcass healthy and safe);

- Been slaughtered in compliance with regulations (particularly in terms of animal protection).

Consequences of media coverage of slaughterhouse mistreatment for official controls

- Audits of all French slaughterhouses: immediately after the videos were published, the then Minister of Agriculture, Stéphane Le Foll, asked prefects to carry out an animal protection inspection of all French slaughterhouses – 259 establishments at the time – within one month. The audit, published in May 2016, reported that[27] :

- 69% of plants had a satisfactory (20%) to acceptable (49%) level of animal protection control; the level of risk control was judged insufficient in 31% of cases; the most serious non-conformities led to immediate action, up to and including shutdown of operations: this concerned 19 slaughter lines, i.e. less than 5% of all inspected lines;

- Progress was to be made in terms of staff training and internal control of the effectiveness of animal protection measures, as operators were not always able to prove all taken animal protection measures.

- Progress was still needed in terms of staff training and internal control of the effectiveness of animal protection measures, as operators were not always able to prove all taken animal protection measures.

📌One Health/One Welfare

The “One Health” or “One Welfare” concept also applies to slaughterhouses, where working conditions can be difficult. A 2003 study[28] on the working conditions in slaughterhouses in Brittany revealed that 89% of men and 92% of women had suffered from a musculoskeletal disorder (MSD) in the previous twelve months. This constant pain, which can cause irreversible impairments, undoubtedly has an impact on the quality of animal handling. What’s more, the daily confrontation with the violence of killing animals leads 40% of men and 45% of women to declare that their work is psychologically demanding..

- Creation of a commission of inquiry into slaughter conditions: chaired by MP Olivier Falorni, this parliamentary commission of inquiry set out to assess abattoirs’ slaughter conditions. To this end, it held some forty hearings with industry players and carried out field visits, some of them unannounced The report contains 65 proposals for changing practices to improve animal protection during the sensitive slaughter process. Some of these measures were quickly taken up and implemented, notably the creation of an ethics committee and the introduction of a video surveillance experiment.

- Creation of a Comité national d’éthique des abattoirs (CNEAb): this was set up in 2017 after the Minister of Agriculture and Food Sovereignty[29] had seized the Conseil national de l’alimentation (CNA). This independent advisory body is a tool to support public decision-making. It is also tasked with issuing opinions for decision-makers and various players in the food industry.

- Video surveillance experimentation: the so-called “Egalim” law, enacted in 2018, incorporated the implementation of a video surveillance system within slaughterhouses in a voluntary and experimental framework, for a period of two years[30].

The evaluation report on this experiment, published in June 2021, indicates that only five slaughterhouses have volunteered. However, the conclusions are unanimous: “They are unanimously satisfied with the system, which they find useful and practical. No one wants to abolish it “. The authors of the report conclude “the video inspection system is a tool for progress, helping to reduce non-conformity in animal protection control procedures in slaughterhouses“[31].

Although not part of this scheme, many other French slaughterhouses are experimenting with or using video surveillance, including for increasing their level of animal protection control.

CECILE BOURGUET, DOCTOR IN ETHOLOGY AND STRESS PHYSIOLOGY

Did you know?

The presence of video surveillance systems in certain live animal handling areas is required to obtain levels A and B of the Animal Welfare Label. This label, based on a set of indicators assessing the entire life of the animal from birth to slaughter, currently only concerns broilers. [32].

- Creation of the mistreatment in slaughterhouses offense: the Egalim law extends the offence of mistreatment in the course of a professional activity to slaughterhouses and doubles the penalties incurred.[33]. From now on: ” Any person operating […] a slaughterhouse […] who mistreats or allows mistreatment of animals in his/her care without necessity is liable to one year’s imprisonment and a €15,000 fine” (article L215-11 of the French Rural and Maritime Fishing Code).

In addition, individuals responsible for mistreatment of animals are also liable to the additional penalties of being banned, permanently or otherwise, from owning an animal and from exercising, either permanently or temporarily (in the latter case for a period not exceeding five years) a professional or social activity involving animals.

📌Infringements specific to slaughterhouse operations

Failure to immobilize animals prior to stunning, bleeding or suspending a conscious animal, or performing ritual slaughter without having been authorized to do so, constitutes a 4th-class contravention punishable by a €750 fine ((article R215-8 of the French Rural and Maritime Fishing Code).).

As the increase in control pressure is limited by the shortage of staff in the veterinary services[34], these new devices are an important complement to animal protection controls in slaughterhouses.

Conclusion

The entry into force of European regulations ten years ago has led to greater consideration being given to animals in the special context of slaughterhouses: standardized operating procedures, the presence of an Animal Protection Officer, compulsory training for all operators, and so on.

However, several acts of mistreatment that occurred in slaughterhouses and were publicized in the media led lawmakers to change national regulations too, notably by creating the offence of mistreatment in a slaughterhouse.

To minimize the physical and psychological suffering of animals in slaughterhouses, in addition to exemplary sanctions, regulations and operator training must evolve simultaneously to take into account new knowledge resulting from research into animal behavior and sensitivity.

In short

Article reviewed and corrected by Cécile Bourguet, PhD in ethology and stress physiology, head of the Bureau Etudes et Travaux de Recherche en Ethologie et Bien-être Animal (ETRE), author of several scientific publications on the subject of animal protection in slaughterhouses.

[1] Rapport n°4038 fait au nom de la commission d’enquête sur les conditions d’abattage des animaux de boucherie dans les abattoirs français

[2] Maurice Agulhon, « Le sang des bêtes : le problème de la protection des animaux en France au XIXème siècle », Romantisme n° 31, 1981, https://www.cairn.info/criminologie–9782340063105-page-178.htm

[3] De la place de l’inspection vétérinaire en abattoir en santé publique vétérinaire. Évolutions et perspectives. Anne-Marie Vanelle. Bulletin de l’Académie Vétérinaire de France Année 2018 171-2 pp. 106-116

[4] Agriculture.gouv.fr : La protection animale dans les abattoirs de boucherie en France

[5]https://www.franceagrimer.fr/content/download/70466/document/FICHE_FILIERE_VOLAILLE_DE_CHAIR%202023.pdf

[6]https://agreste.agriculture.gouv.fr/agreste-web/download/publication/publie/Chd2215/cd2022-15_SAA_2021D%C3%A9finiifV2.pdf

[7] Règlement (CE) N° 1099/2009 du Conseil du 24 septembre 2009 sur la protection des animaux au moment de leur mise à mort

[8] R214-63 à R214-81 du Code rural et de la pêche maritime, Arrêté du 12 décembre 1997 relatif aux procédés d’immobilisation, d’étourdissement et de mise à mort des animaux et aux conditions de protection animale dans les abattoirs

[9]Règlement (CE) n°1099/2009 : article 6

[10] Règlement (CE) n°1099/2009 : article 6

[11] https://agriculture.gouv.fr/le-plan-gouvernemental-pour-la-protection-et-lamelioration-du-bien-etre-animal

https://www.defenseurdesdroits.fr/sites/default/files/atoms/files/ddd_guide-lanceurs-alertes_maj2023_20230223.pdf

[12] Règlement (CE) n°1099/2009 : articles 7 et 21, Arrêté du 31 juillet 2012 relatif aux conditions de délivrance du certificat de compétence concernant la protection des animaux dans le cadre de leur mise à mort

[13] Règlement (CE) n°1099/2009 : annexe III – 1.9

[14] Claudia C. Terlouw, Cécile Bourguet, Véronique Deiss. La conscience, l’inconscience et la mort dans le contexte de l’abattage. Partie I. Mécanismes neurobiologiques impliqués lors de l’étourdissement et de la mise à mort. La revue française de la recherche en viandes et produits carnés, 2015, 31 (2-2), pp.1-20.

[15] Règlement (CE) n°1099/2009 : article 4, Code rural et de la pêche maritime : article R214-70

[16] Terlouw C., Bourguet C., Deiss V., 2016a. Consciousness, unconsciousness and death in the context of slaughter. Part I. Neurobiological mechanisms underlying stunning and killing. Meat Sci., 118, 133-146.

Terlouw C., Bourguet C., Deiss V., 2016b. Consciousness, unconsciousness and death in the context of slaughter. Part II. Evaluation methods. Meat Sci., 118,147-156.

Terlouw, E.M.C., Ducreux B., Bourguet, C., 2021a. Particularités neurobiologiques et physiologiques des différentes techniques d’abattage – Abattage avec et sans étourdissement : conscience et induction de l’inconscience (partie 1). Viandes & Produits Carnés, VPC-2021-3725.

Terlouw, E.M.C., Ducreux B., Bourguet, C., 2021b. Spécificités des indicateurs de conscience et d’inconscience selon les méthodes d’abattage. Abattage avec et sans étourdissement : évaluation pratique de l’inconscience (partie 2). Viandes & Produits Carnés, VPC-2021-3726

[17] Règlement (CE) n°1099/2009 : article 4.4, Code rural et de la pêche maritime : articles R214-70 et 73

[18] Code rural et de la pêche maritime : articles R214-70 et 75, Arrêté du 28 décembre 2011 relatif aux conditions d’autorisation des établissements d’abattage à déroger à l’obligation d’étourdissement des animaux

[19] EFSA Panel on Animal Health and Welfare. Welfare of cattle at slaughter. EFSA J. 2020, 18, 6275

[20] Arrêté du 31 juillet 2012 relatif aux conditions de délivrance du certificat de compétence concernant la protection des animaux dans le cadre de leur mise à mort – Annexe II

[21] Source interne DGER

[22] Depuis 2023, c’est la Chaire bien-être animal qui assure la mission d’instruction technique des demandes d’habilitation pour le compte de la DGAL.

[23] Arrêté du 30 décembre 2011 relatif à la participation du personnel de l’abattoir au contrôle de la production de viande de volailles et de lagomorphes

[24] Instruction technique DGAL/SDSSA/2022-62 relative à l’organisation des contrôles officiels relatifs à la protection animale en abattoir au moment de la mise à mort et des opération annexes.

[25] Règlement d’exécution (UE) 2019/627 de la Commission du 15 mars 2019 établissant des modalités uniformes pour la réalisation des contrôles officiels en ce qui concerne les produits d’origine animale destinés à la consommation humaine conformément au règlement (UE) 2017/625 du Parlement européen et du Conseil et modifiant le règlement (CE) n° 2074/2005 de la Commission en ce qui concerne les contrôles officiels (Texte présentant de l’intérêt pour l’EEE.)

[26] Agriculture.gouv.fr : La santé au travail des agents de l’État en abattoir : une approche sociologique – Analyse n°133

Les missions des services de l’Etat dans les abattoirs

[27] https://www.editions-legislatives.fr/actualite/protection-animale-dans-les-abattoirs-d-animaux-de-boucherie/

[28] État de santé des salariés de la filière viande du régime agricole en Bretagne

[29] Conseil National de l’Alimentation – avis 82

[30] Agriculture.gouv.fr : Lance de l’expérimentation du contrôle par vidéo dans les abattoirs

[31] Comité de suivi et d’évaluation de l’expérimentation du dispositif de contrôle par vidéo dans les abattoirs tel que prévu par l’article 71 de la loi du 30 octobre 2018

[32] https://www.etiquettebienetreanimal.fr/les-criteres-de-letiquette/

[33] LOI n° 2018-938 du 30 octobre 2018 pour l’équilibre des relations commerciales dans le secteur agricole et alimentaire et une alimentation saine, durable et accessible à tous : article 67

[34] Question écrite au Senat n°06095 – Insuffisance de la présence de vétérinaires le long de la chaîne d’abattage

Keep in mind

- In France, animals are protected, including in slaughterhouses

- In French slaughterhouses, "animal protection" is the relevant terminology, not "welfare".

- Regulations call for appropriate equipment, trained personnel, daily checks and increased penalties in the event of violations

Key Figure

This is the number of slaughterhouses for meat animals (pigs, cattle, sheep, goats and horses) in France.