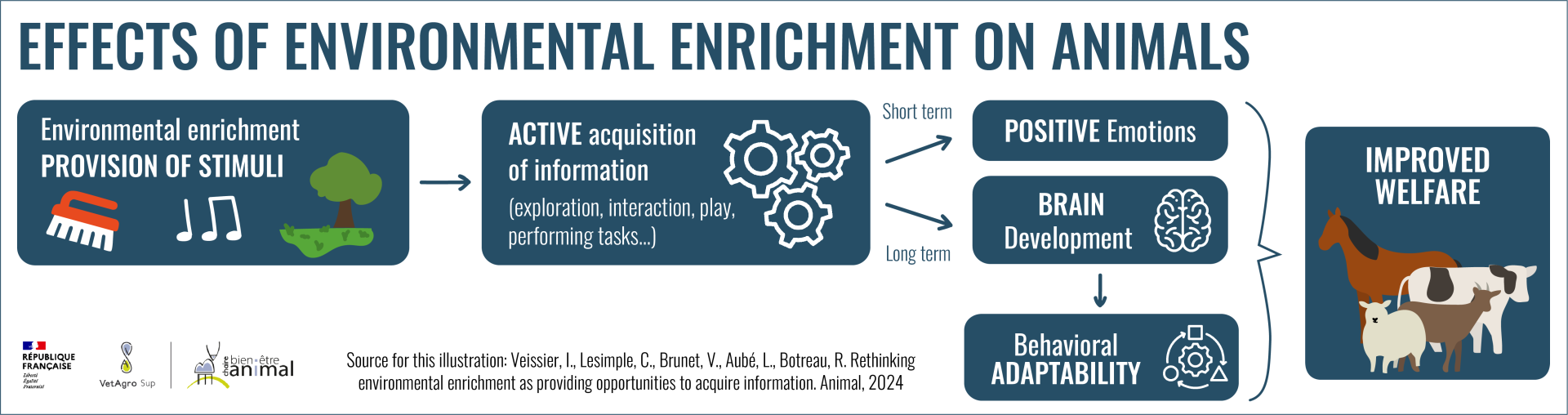

Keep in mind

- Environmental enrichment refers to modifications that aim to make the animals' environment more complex: it provides information, stimulates the animals and increases their propensity to explore.

- Enrichment is a complement to – and not a replacement for – the fulfillment of basic needs.

- Enrichment induces positive effects in the short term (positive emotions) and in the long term (adaptability, resilience)

In a literature review published in the summer of 2024, Isabelle Veissier and her colleagues[1] reviewed the current state of scientific knowledge on environmental enrichment. The Chaire BEA team is pleased to provide you with a popularized summary.

In livestock farming, the environment in which animals live is often less stimulating than their natural habitat. While legislation requires their basic biological needs (eating, sleeping, drinking, etc.) to be fulfilled, it does not often impose enrichments that would allow varied cognitive experiences for the animals.

Definition of enrichment

What is enrichment?

Environmental enrichment refers to modifications aimed at making captive animals’ impoverished environment more complex.

Indeed, a poor environment, even if it allows the satisfaction of basic needs, may not allow complete expression of an animal’s behavioral repertoire. It can thus be a source of boredom, which can lead to the development of abnormal behaviors (stereotypies, aggressiveness, apathy, etc.). First developed to improve the cognitive abilities of captive animals in zoos or for scientific research, environmental enrichment has more recently been used on farm animals to reduce boredom and abnormal behaviors.

Types of enrichment

Different types of enrichment

Sensory enrichment aims to stimulate one or more of an animal’s senses . This can be visual, auditory, olfactory, tactile or gustatory stimulation; alone or in combination. Thus, certain stimuli can encourage activity and the search for their source: for example, country music in cows[2], the movement of a laser pointer in chickens[3], or the smell of peppermint and rosemary in many species (primates, mice, dogs, chickens, etc.)[3]

Feeding-based enrichment aims to vary not only the nature of the offered food, but also the means of accessing it. For example, in lambs[6] and horses[7],

choosing feed led to an increase in consumption and reduced the appearance of abnormal behavior, compared with the control group, which was always offered the same feed. The use of “slow feeders” devices designed to increase feeding time without changing the distributed quantity of feed, such as hay nets, also reduces the expression of abnormal behavior in horses[8].

Social enrichment (intra- or inter-specific) consists in offering the opportunity to interact with congeners or animals of other species, including humans. Indeed, opportunities for interaction are really important for social species such as farm animals. Young animals are particularly sensitive to their social environment, which, when adapted, enables the development of indispensable social and cognitive skills. Conversely, isolation during this period can result in animals unable to recognize and understand social signals, making them more aggressive. It also increases reactivity to stressful events, promotes anxious behavior and reduces cognitive capacity. It has been shown that horses individually housed express less abnormal behavior when they can have physical and visual contact with congeners, using partially open partitions[9]. Contact with caretakers can also play a role in social enrichment, particularly in the absence of contact with congeners. Thus, kid goats[10] and piglets[11] that experience positive human contact not only are more attracted to humans: they are also less reactive when isolated, suggesting that human contact affects their emotional reactivity.

Did you know?

Stereotypies are defined as repetitive, invariant behaviors, without any apparent purpose or function. Examples: a captive feline that moves back and forth in its enclosure, a bird that plucks its own feathers (self -pecking), a horse repeatedly shifting its weight between forelimbs (weaving), etc.

Environmental enrichment can thus take many different forms: it can be sensory, physical, social, occupational, cognitive, feeding-based or a mixture of the above. Furthermore, one type of enrichment does not exclude another and the introduction of a new food, for example, may be both dietary and sensory enrichment.

Simple examples of enrichment:

- Playing music in a livestock building

- Adding a new feed (fruit, vegetable, fodder) in addition to the daily ration

- Installing brushes for animals to scratch

- Positive interactions with humans

In this light, can any modification of the environment in favor of animal welfare be considered as enrichment?

Improvement vs enrichment

Environmental improvement or enrichment?

Enrichment was first described as “Any improvement in the biological functioning of captive animals resulting from modifications of their environment” [12] . However, it is now distinguished from modifications which, although improve animal welfare, simply allow the animal’s needs or preferences to be fulfilled [13]. This is the case, for instance, when providing substrate to chickens so that they can take dust baths.

Enrichment goes further, by inducing a change/addition in the environment that provides information (sensory, social, etc.) that the animal perceives and can process. To obtain this information, the animal must resort to investigation, experience or practice. Thus, enrichment is effective if, through specific properties linked to its complexity, it stimulates the animal and increases its propensity to explore. Going back to the example of chickens, this could involve, for example, placing small straw bales on the ground in livestock buildings: in addition to meeting certain basic needs by providing a perch and resting area (chickens like to lie down on it), straw bales stimulate exploration by encouraging chickens to peck at the straw.

In other words, the arrangements made to enrich an animal’s environment cannot compensate for a sub-optimal environment: they therefore come as a complement and not as a replacement for the satisfaction of basic needs.

While environmental improvement has a direct positive impact on animals, environmental enrichment has, on top of that, an indirect and delayed effect that extends beyond the time spent in contact with the object in question. This difference is due to the fact that enrichment, unlike improvement, is a modification of the environment that allows animals to acquire abilities that they can mobilize later on.

Effects of enrichment

What are the effects of environmental enrichment on animals?

As we have seen previously, environmental enrichment has a direct and immediate impact on animals: it induces a reduction in the occurrence of abnormal behaviors and aggressiveness. By stimulating curiosity, it pushes animals to explore. Adding new elements therefore not only directly promotes exploration but also encourages animals to better explore their environment!

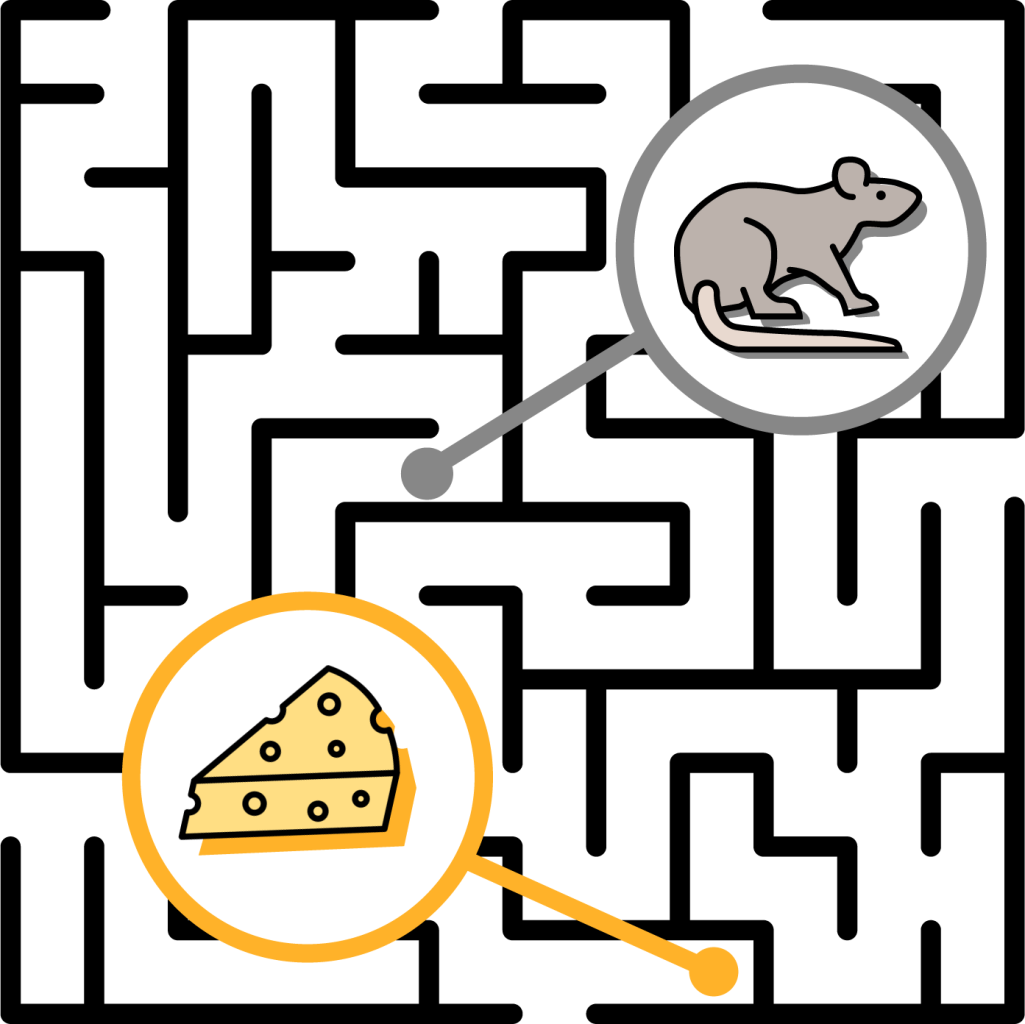

Beyond the meaning of the object being explored, it is exploration itself that seems to be rewarding for the animals. It has been shown that rats prefer to explore a maze without knowing if there will be a reward, rather than taking known routes that they know will lead to a food reward[14] ! Similarly, a study has highlighted that piglets prefer to enter an enclosure in which they know that a new object is hidden, rather than an enclosure where they have learned that a familiar object is hidden[15] . They therefore prefer to explore and interact with unknown objects!

It is interesting to note that animals are not only able to perform tasks to get access to food; they also seem interested in performing the tasks themselves. It has been shown that monkeys given tasks of increasing difficulty do not systematically eat their food reward before moving on to the next problem: success is already a reward in itself[16] . In cognitive science, the signs of excitement that accompany the resolution of a task have a name: the “Eureka effect“.

Did you know?

Contrafreeloading is the phenomenon in which an animal prefers to make an effort to obtain a food reward rather than freely accessing this same reward. This mechanism has been demonstrated in many species (rodents, birds, primates) including livestock (goats, heifers).

Although very surprising, its function may be to ensure that the task always allows the reward to be obtained. By acting in this way, the animal collects information that could be useful in the event of a change in its environment: it is therefore an adaptive behavior [17].

This concept is to be compared with the notions of predictability and control of the environment, perceived positively by animals.

This active search for information also induces many long-term effects: reduction of neophobia (i.e. a reduction in the fear of novelty, which results in an increase in curiosity), better performance in learning and memorizing information, development of better strategies and behavioral flexibility (ease in changing strategies).

By stimulating brain development and the proliferation of cells and their connections, environment exploration therefore induces an improvement in all of the animal’s cognitive capacities as well as adaptation to the environment.

Knowing this, what stimuli should we choose in practice and under what conditions should we make them accessible to animals for maximum effectiveness?

Key elements for implementation

The key elements for setting up effective enrichment

Nature du stimulus

The stimulus can be natural or artificial: it is not necessary to use elements from the animal’s natural living environment. A laser pointer, although it has no biological significance for chickens, is an effective enrichment.

More than the stimulus itself, it is the way of interacting with it that must match the animal’s natural behavior and stimulate its species’ privileged sensory capacity: for example, while chickens will preferentially interact with their beak and pigs with their snout, primates will explore an object primarily with their hands.

Important

It is essential to ensure that the element added to the animals' environment as enrichment is not likely to endanger them (injuries, illnesses, poisoning, etc.).

Furthermore, making the environment more complex by adding stimuli does not always improve animal welfare: it is easy to understand that adding the smell of a predator will not set off positive emotionnal responses…

However, without going to such extreme cases, the stimulus can be positive, neutral but also, in a moderate way, negative. Indeed, one of the factors that seems to distinguish positive stress (a challenge) from negative stress (a dead end) induced by a task, seems to be the animal’s ability to cope with the situation, to find a solution.

Stimulus effectiveness

For enrichment to be effective, the task the animal is subjected to, the difficulty it faces, must therefore imperatively be in line with its cognitive and behavioral capacities. Adequation of the difficulty is essential: if the task is too simple, the animal will lose interest in it; if it is too complex, it can generate anxiety.

Thus, the effectiveness of enrichment is based on both complexity and variability. Complexity is defined by the number of characteristics needed to describe the enrichment (number of objects added to the enclosure, number of different materials that make up the object, diversity of sensory stimulations, number of congeners added, etc.).

Variability is also a key factor because it ensures a continuous flow of information acquisition. Habituation can occur quickly and thus limit the effects of enrichment. Therefore, regular checks on the animals’ interest in and interaction with enrichment measures should be carried out and, if necessary, they should be changed regularly.

Finally, it should be noted that enrichment can be effective even if access to it is limited!

Examples of effective enrichment in livestock farming

The European Union Reference Centre for the Welfare of Ruminants and Equines (EURCAW Ruminants & Equines) has produced thematic factsheets, which present the enrichments having a significant effect on the welfare of each species:

🐄 Environmental enrichment for cattle

🐎 Environmental enrichment for equines

🐑 Environmental enrichment for sheep

🐐 Environmental enrichment for goats

🐔 Environmental enrichment for poultry (coming soon)

Individual adaptation of the stimulus

While there are broad principles that apply at the species level, it is important to remember that the benefits of enrichment depends on individuals. One must therefore find the right balance between curiosity and neophobia.

Indeed, when they express curiosity, animals expend energy and take risks (getting poisoned by consuming a harmful food, getting injured, being attacked, etc.): curiosity therefore comes at a price! Conversely, neophobia, from the ancient Greek neos (“new”) and phóbos (“flight, fear”) – literally “the fear of what is new” –, is a protection mechanism against potential harm. Animals therefore express curiosity when the supposed benefits are deemed greater than the risks. This may explain, for example, why pregnant ewes, when fed their usual ration simultaneously in their usual trough and in a new device (hay net), reject the new device while non-pregnant ewes use it from day one. Animals with high energy needs may be less curious because they are less inclined to take risks.

In addition to physiological stage, age also appears to be an important factor: young animals are likely to benefit more from enrichment because they tend to be more curious and have better brain plasticity than adult animals.

It is therefore advisable to carefully observe the animals’ reactions to the proposed enrichments and adapt them accordingly.

Conclusion

Environmental enrichment aims to provide animals with opportunities to acquire information by actively interacting with their environment. In the short term, this process of acquiring information induces positive emotions in animals, which are then more inclined to explore their environment. This has the longer term consequence of stimulating their cognitive abilities (learning, memory) and thus improving their ability to adapt to their environment. Better equipped to manage future changes, animals that benefit from enrichment demonstrate greater adaptability and are therefore more resilient.

If the effectiveness of enrichments put in place depends on the species, and therefore requires a good knowledge of it, this is not enough: in fact, preferences vary from one individual to another but also during the life of an individual (experience, physiological stage, age, etc.)! It is therefore appropriate to adapt to each individual according to its expressed signs of well-being or discomfort.

[1] Université Clermont Auvergne, INRAE, VetAgro-Sup, UMR Herbivores

[2] Uetake, K., Hurnik, J.F., Johnson, L., 1997. Effect of music on voluntary approach of dairy cows to an automatic milking system. Applied Animal Behaviour Science 53, 175–182.

[3] Lourenço da Silva, M.I., Almeida Paz, I.C.d.L., Jacinto, A.S., Nascimento Filho, M.A., Oliveira, A.B.S.d., Santos, I.G.A.d., Mota, F.d.S., Caldara, F.R., Jacobs, L., 2023. Providing environmental enrichments can reduce subclinical spondylolisthesis prevalence without affecting performance in broiler chickens. Plos One 18, e0284087.

[4] Lesimple, C., Reverchon-Billot, L., Galloux, P., Stomp, M., Boichot, L., Coste, C., Henry, S., Hausberger, M., 2020. Free movement: a key for welfare improvement in sport horses? Applied Animal Behaviour Science 225, 104972.

[5] Palstra, A.P., Planas, J.V., 2011. Fish under exercise. Fish Physiology and Biochemistry 37, 259–272.

[6] Garrett, K., Beck, M.R., Marshall, C.J., Maxwell, T.M.R., Logan, C.M., Greer, A.W., Gregorini, P., 2021. Varied diets: implications for lamb performance, rumen characteristics, total antioxidant status, and welfare. Journal of Animal Science 99, skab334.

[7] Thorne, J.B., Goodwin, D., Kennedy, M.J., Davidson, H.P.B., Harris, P., 2005. Foraging enrichment for individually housed horses: practicality and effects on behaviour. Applied Animal Behaviour Science 94, 149–164.

[8] Correa, M.G., Rodrigues e Silva, C.F., Dias, L.A., da Slva Rocha Junior, S., Thomes, F.R., Alberto do Lago, L., de Mattos Carvalho, A., Faleiros, R.R., 2020. Welfare benefits after the implementation of slow-feeder hay bags for stabled horses. Journal of Veterinary Behavior 38, 61–66.

[9] Cooper, J.J., McDonald, L., Mills, D.S., 2000. The effect of increasing visual horizons on stereotypic weaving: implications for the social housing of stabled horses. Applied Animal Behaviour Science 69, 67–83.

[10] Boivin, X., Braastad, B.O., 1996. Effects of handling during temporary isolation after early weaning on goat kids’ later response to humans. Applied Animal Behaviour Science 48, 61–71.

[11] Lucas, M.E., Hemsworth, L.M., Butler, K.L., Morrison, R.S., Tilbrook, A.J., Marchant, J. N., Rault, J.L., Galea, R.Y., Hemsworth, P.H., 2024. Early human contact and housing for pigs – part 1: responses to Humans, novelty and isolation. Animal 18, 101164.

[12] Newberry, R.C., 1995. Environmental enrichment: Increasing the biological relevance of captive environments. Applied Animal Behaviour Science 44, 229–243.

[13] Veissier, I., Lesimple, C., Brunet, V., Aubé, L., Botreau, R. Rethinking environmental enrichment as providing opportunities to acquire information. Animal, 2024. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.animal.2024.101251

[14] Franks, B., Champagne, F., Higgins, E., 2013. How enrichment affects exploration trade-offs in rats: implications for welfare and well-being. Plos One 8, e83578.

[15] Wood-Gush, D.G.M., Vestergaard, K., 1991. The seeking of novelty and its relation to play. Animal Behaviour 42, 599–606.

[16] Watson, S.L., Shively, C.A., Voytko, M.L., 1999. Can puzzle feeders be used as cognitive screening instruments? differential performance of young and aged female monkeys on a puzzle feeder task. American Journal of Primatology 49, 195–202.

[17] Inglis, I.R., Forkman, B., Lazarus, J., 1997. Free food or earned food ? A review and fuzzy model of contrafreeloading. Animal Behaviour 53, 1171-1191 https://doi.org/10.1006/anbe.1996.0320