True… although not always

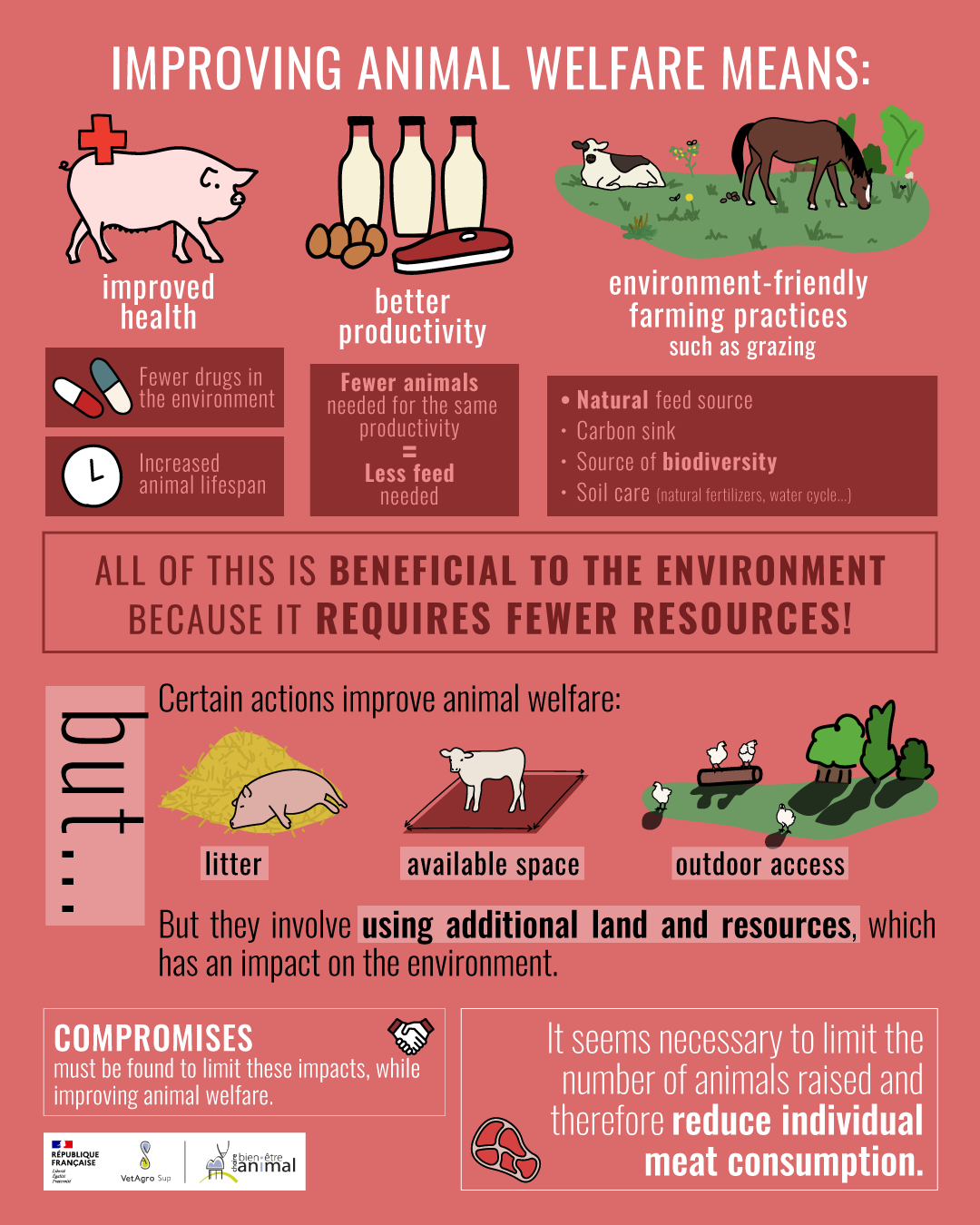

Improving animal welfare can have positive effects on animal productivity and health, thereby contributing positively to the environment, climate, and biodiversity. However, in some cases, these improvements can also increase the environmental impact of livestock farming. It is therefore necessary to find compromises to reconcile animal welfare and environmental protection. From this perspective, reducing meat consumption seems to be a prerequisite.

Keep in mind

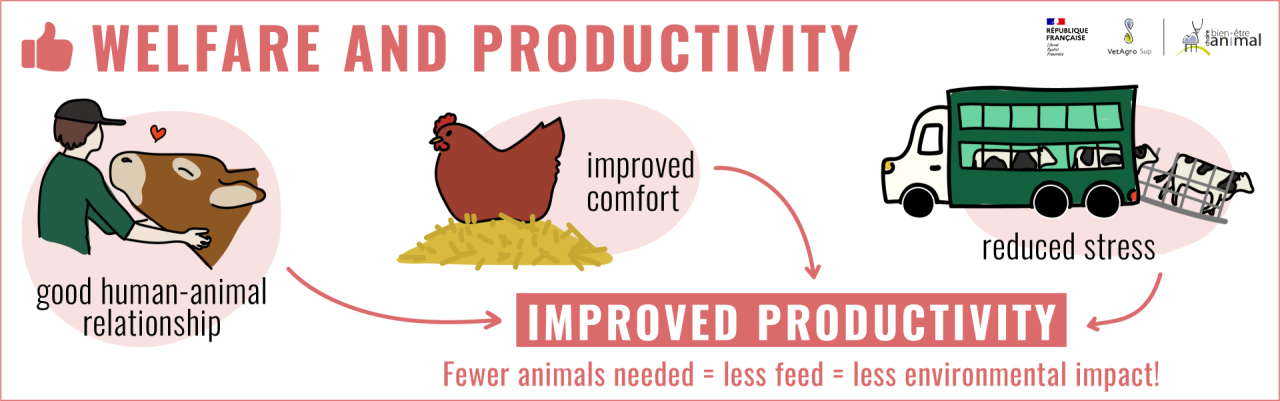

- Improving animal welfare improves their productivity: fewer animals are needed to produce the same amount of meat, milk, eggs, etc., which limits the negative impacts of livestock farming.

- Improving animal health reduces the use of drugs and lowers their environmental impact.

- Some farming practices, such as grazing, are beneficial for animals and the environment.

- Increased space, bedding, and outdoor access are essential for animal welfare but have an impact on the environment.

This article aims to review the impact of changes in farm animal welfare on the environment, in regards to greenhouse gas emissions but also biodiversity, the use of agricultural land, and inputs (straw, feed, etc.).

One way to improve animal welfare while limiting negative impacts on the environment would be to reduce the consumption of animal products – thus reducing the number of animals raised. However, for this article we will assume that the production and consumption of animal products remains unchanged.

Improved welfare for a preserved environment

Impact on productivity and the environment

Improving animal welfare can have positive consequences on productivity. For example, a good human-animal relationship improves reproductive performance in sows[1] and milk production in dairy cows[2]. Conversely, fear of humans is a factor that reduces feed efficiency in broiler chickens, growth in piglets[3] and milk production in dairy cows[4].

Similarly, improving animal comfort has a positive impact on their productivity. When dairy cows are more comfortable, they suffer fewer injuries, are less dirty and less prone to lameness[5] and also produce more milk of a higher quality.

The importance of welfare is also evident when animals are transported to the slaughterhouse or at the time of slaughter: stress in animals has a negative impact on the quality of pork, beef, poultry and fish[6]. Meat quality defects caused by animal stress can result in the meat being unfit for human consumption. Raising animals for their meat before ultimately putting it to waste is an under-achievement, to say the least!

If animal welfare improves productivity, it is then possible, for a given production, to reduce the number of animals needed. Similarly, less feed will be needed to achieve the same production. Reducing total feed reduces the impact on the environment, as less agricultural land is needed to grow it (including, in some cases, deforestation and pesticide use), and it also reduces the use of fossil fuels and associated emissions (for cultivation, fertilizer production, harvesting, transportation, etc.) as well as water consumption (for irrigation).

Animal welfare gains therefore increase productivity, which in turn reduces the environmental impact of livestock farming.

Impact on animal health and the environment

Healthier animals are more productive

Animal welfare also has consequences for animal health. Poor welfare weakens the immune system, making animals more vulnerable to disease. This is why health criteria are used as a welfare indicator.

Poor welfare can be associated with higher animal mortality, as is the case with dairy cows[7]. Conversely, piglets raised in a suitable, enriched social environment show less susceptibility to respiratory diseases than piglets raised in a stimulus-poor environment. Animals that are less prone to disease are more productive, which is beneficial for the environment. For example, treating sheep for footrot (a hoof disease) reduces lameness, improves their welfare, and also improves reproductive performance and lamb growth[8].

A 2022 study by the British research institute Moredun[9] suggests that a 10% reduction in greenhouse gases from cattle and sheep farming can be achieved simply by improving animal health.

Healthier animals need fewer drugs

In addition, deteriorating animal health often leads to increased use of drugs, including antimicrobials[10] (antibiotics, antiparasitics). These may be released in the environment, which can harm certain bacterial populations and promote the emergence of resistant bacteria. The same is true of antiparasitics, which are increasingly causing resistance and are highly toxic, particularly to insects and arthropods such as spiders, millipedes, etc[11][12].

Healthier animals live longer

Welfare and health deterioration can also lead to early culling of animals, thus reducing their expected lifespan. The productive lifespan or “career” of animals – i.e., the period during which an animal produces resources – is then proportionally reduced relative to its unproductive lifespan – i.e., the period during which it has used inputs (feed, bedding, space in buildings, labor time, etc.) and emitted greenhouse gases without producing economic value. This increases the environmental cost of production.

For example, a dairy cow that calves for the first time at 2 years of age has an unproductive life period of 2 years. If it has a normal lifespan and calves six times at a rate of one calving per year, its productive lifespan is six years and the ratio is therefore 3. It will have had a productive lifespan three times longer than its unproductive lifespan: the “initial investment” will therefore have been recouped. Conversely, a cow that calves for the first time at 3 years of age and then calves only twice will have a longer unproductive life period than its productive life period… and will therefore have consumed more resources in relation to the production it will have achieved.

Currently, the average lifespan of dairy cows is 5.75 years, and they are culled after an average of 2.3 lactations. It has been shown that as the age of first calving increases, the average lifespan of a cow increases, but the lactation period and cumulative milk production over its career decrease[13]. Therefore, as the age of first calving increases, productive lifespan decreases.

Increasing the longevity of animals, whether by lowering the age at which they begin to produce economically valuable resources or by increasing the age at which they are culled (provided that their production level remains satisfactory), is therefore ultimately beneficial to the environment.

In addition, extending the productive life of animals makes it possible to maintain equivalent production levels with fewer animals and thus reduce feed requirements. Of course, this aspect of animal longevity only applies to production systems where longevity is beneficial because the animal will produce more calves, more milk, or more eggs, but does not apply to production systems that involve fattening the animal, in which case, reducing the fattening period is beneficial to the environment. It is important, of course, that the reduction in fattening time is not done at the expense of animal welfare, as can be the case, for example, with fast-growing chickens that are slaughtered after 35 days.

Finally, the farming practice of extending the lactation period of cattle or goats limits the number of calves and kids needed for a new lactation period[14]. This contributes to animal welfare by reducing the number of pregnancies required per animal and the number of animals considered to be of “no economic value” that must be slaughtered. It is also beneficial to the environment, as fewer animals raised means fewer resources needed.

Impact of positive farming practices on the environment

Impact of better farming practices on the environment

Certain farming practices improve animal welfare while limiting negative impacts on the environment.

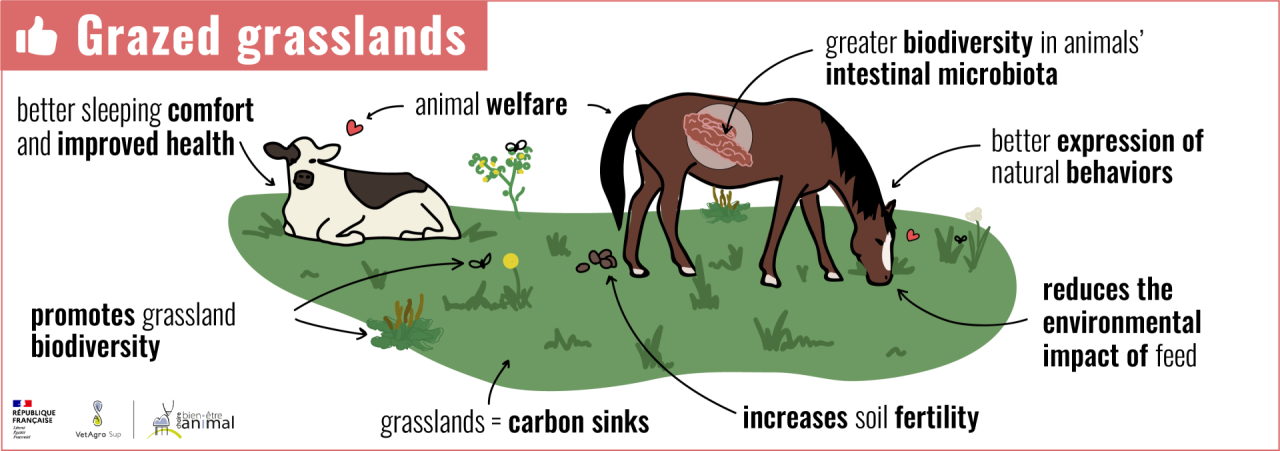

Grazed pastures: a source of natural feed, carbon sinks, a factor in biodiversity and soil health

This is particularly true of pasture-based farming[15] which, under the right conditions, improves animal welfare. Grazing is associated with better expression of certain natural animal behaviors thanks to a richer and more stimulating environment. It also provides animals with more comfortable sleeping areas and improved health[16][17]. In horses, it has been shown that long-term grazing makes for greater biodiversity in animals’ intestinal microbiota and improves their behavior and welfare[18].

From an environmental perspective, grazing reduces the share of purchased feed in the animal’s diet (forage and concentrates that require cultivated land and lead to competition between human and animal food), thereby reducing the environmental impact of feeding. In addition, grasslands are significant carbon sinks that store part of greenhouse gases. Grazing therefore offsets some of the gas emissions associated with ruminant farming[19].

Furthermore, biodiversity in a grazed pasture can be enhanced by applying good practices. Limiting the number of animals per plot and avoiding continuous grazing in favor of crop rotation (which allows flowering) promotes the development of a wide variety of plants and animal species such as butterflies, wild bees, bumblebees, grasshoppers, etc[20] thus contributing to biodiversity. In addition, when in between two crop periods, grazing increases soil fertility through animal urine and feces, which act as fertilizer, provided that their concentration in the soil is not too high[21]. By fertilizing crops – especially in a natural way –, forage yield is improved and the share of concentrates used in feed is reduced. Finally, mixed grazing, which combines different animal species on the same plot (such as cattle and horses, for example), can also be beneficial in that it optimizes the consumption of different species of grass in the pasture due to the complementary feeding choices of different herbivores, all the while minimizing parasite infestation – which is beneficial to the health and welfare of the animals[22].

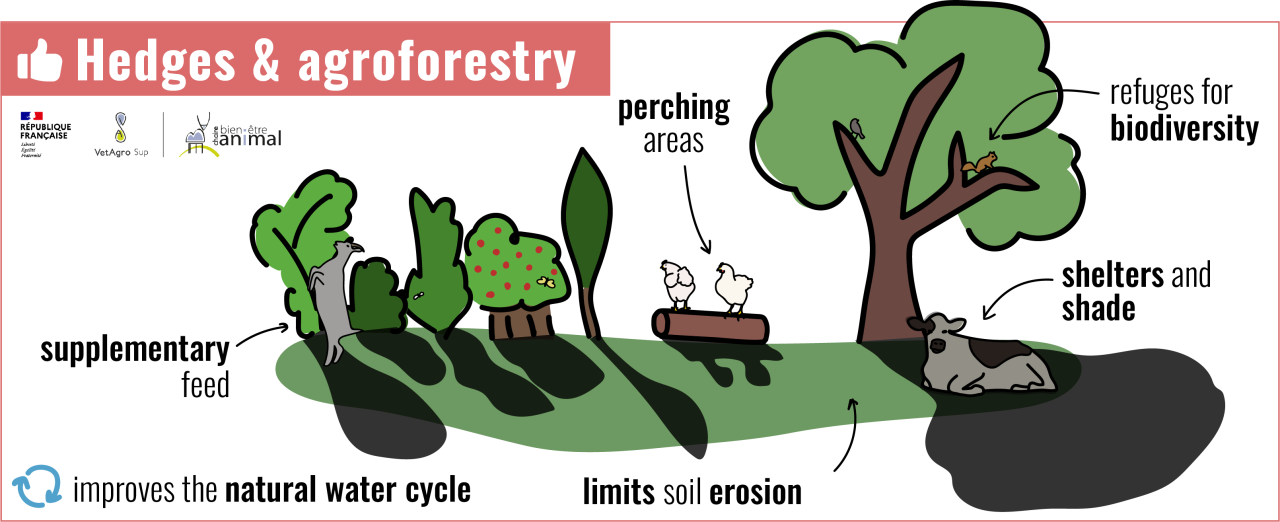

Hedges and agroforestry: everyone wins

Other co-benefits of grazing promote animal welfare and environmental conservation. When pastures are surrounded by hedges and trees, they provide animals with shelter and shade, perching areas for poultry and goats (which reduces their stress and allows them to express their natural behavior), supplementary feed (via berries and foliage) while providing refuges for biodiversity, limiting soil erosion, improving the natural water cycle, etc[23]. In this sense, agroforestry, which combines trees, crops, and animals on the same plots of land, meets the dual objective of combining environmental health and animal welfare.

Bedding, essential for the expression of animal behavior and a natural fertilizer

Good practices are also important indoors. This applies particularly to bedding and to the proper management of urine and feces, which allow animals to express natural behaviors more easily, improve comfort and cleanliness, and reduce injuries, thereby enhancing overall welfare. Although the production of bedding does have an environmental impact, we will later see that once used, it can be recycled as an organic fertilizer for soils and crops, contributing to a virtuous ecological cycle.

Of course, this possible positive impact on the system depends on bedding thickness, how often it is replaced, how it is spread on cultivated land, etc. Urine and feces management is easier when animals are raised indoors rather than outdoors. For example, collecting feces through a slurry pit allows, via methanization, the production of biogas used as an energy source, and also digestate – used as compost on crops. Urine from cattle can be collected and stored in a closed tank (to prevent the volatilization of ammonia in its gaseous form) and then used as a mineral fertilizer for cultivated land.

Managing urine and feces in buildings and spreading it accurately also makes it possible to better manage the concentration in the soil and groundwater of certain chemical elements such as nitrates, which are pollutants if present in excessive quantities.

Improving animal welfare can also be detrimental to the environment

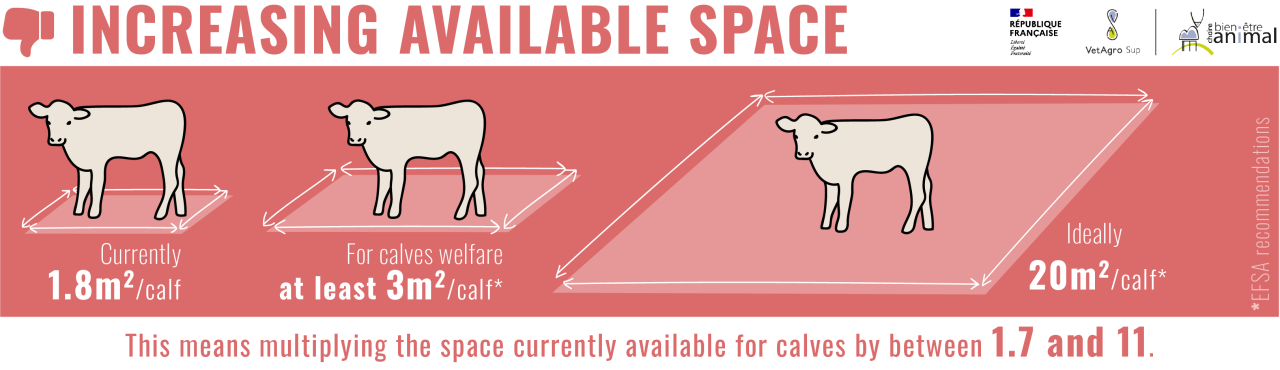

Increasing available space

One of the major sources of improvement in animal welfare is the increase in available space and the reduction in density. For example, in its latest scientific opinion on calf welfare published in 2023[24], the EFSA estimates that the regulatory space allowance of 1.8 m² per calf does not allow them to express their locomotor or play behavior. The EFSA estimates that increasing the available space to 20 m² per calf would be fully conducive to their welfare and that 3 m² per calf should be a minimum. This equates to multiplying the space currently available for calves by between 1.7 and 11. In 2023, just over 1 million calves were slaughtered in France. The space required to raise them was approximately 1.8 million m² of buildings. Increasing the space available to 3 m² would require 1.2 million m² of additional livestock buildings in France… and much more if the regulatory space were increased to 20 m² per calf.

Similarly, the European “End of Cages” initiative advocates ending the use of cages for animal farming. Currently, European regulations require that a laying hen in a cage has 750 cm² of space, meaning that just over 13 hens can be raised per m² of cage space. In barn housing, with no access to the outdoors, the regulatory density is 9 hens per square meter. If cage rearing were to be abolished tomorrow and the space required for hens in buildings remained unchanged, the area required would have to be multiplied by 1.4. However, according to European data[25], if all these hens were to be reared on the ground, the total building area would have to increase from 11.3 million square meters to 16.6 million square meters, i.e., more than 5 million square meters of additional space, equivalent to 500 hectares of indoor building space.

Increasing space would undoubtedly have a positive effect on welfare, but also negative impacts on the environment, both in terms of land use and resource use, particularly in relation to construction materials[26] and the energy needed to heat the buildings. More land use for livestock buildings means using space devoted to other uses, such as crops, grasslands, forests, wasteland, and more generally, areas conducive to biodiversity. It also increases the fragmentation of natural habitats, limiting the connection between different areas for wildlife populations.

Admittedly, an additional 500 hectares for laying hens at the European level may seem little compared to the 157.4 million hectares of usable agricultural land in Europe in 2023[27]. However, these 500 hectares of new buildings would have surrounding areas attached, and this would all be added to the rest of the total animal production (not just laying hens). Furthermore, such a scenario does not take into account the current proposal to also reduce the density of laying hens in buildings from 9 hens per m² to 6 hens per m², which would require more than doubling the total surface area of buildings compared to cage rearing. This question ties in with that of “land sharing – land sparing” theorized in the model by Green et al. (2005)[28] : “Should agriculture be intensified in order to preserve more natural areas rich in biodiversity, or should we favor more extensive agriculture that is less economical in terms of natural areas?“. One solution to limit the increase in land dedicated to livestock farming while increasing the space available per animal would be to reduce the number of animals raised, thereby accepting a reduction in production in order to do less but better. This also applies to the use of bedding.

Increasing the amount of bedding

Improving animal welfare, whether by providing more space or better floor comfort, requires an increased need for bedding. Thus, switching from a cage system with wire mesh flooring to a straw-based barn system, or from a slatted floor system to a litter system, would require more litter.

In pigs, for example, deep litter systems clearly improve animal welfare, increasing exploratory behavior, with more frequent positive social behaviors, and fewer carpal and tarsal lesions[29]. However, deep litter requires between 20 and 25 kg of straw per pig at the start of rearing, followed by regular strawing up. For the duration of fattening on deep litter, the amount of straw varies between 60 and 100 kg per pig[30]. However, French production of pigs for slaughter was 22 million head in 2023[31], of which approximately 90% (i.e., almost 20 million pigs) were raised on fully slatted floors, i.e., without bedding. Providing deep litter for all these animals would require at least 1.2 million additional tons of straw. Again, this may seem little compared to the 14.5 million tons of straw produced in France in 2023[32]. But here we only mentioned pigs for meat here, not sows – whose needs are even greater – let alone other animals. The straw market is already under pressure, and new uses, including non-agricultural ones, also require straw.

Increasing the amount of bedding to improve animal comfort will therefore undoubtedly require an increase in the surface of cereal crops to produce straw… to the detriment of other crops. Furthermore, in order for the bedding to remain clean, the area available per pig in bedding must be greater than the space available on slatted flooring.

Access to the outdoors

Another key factor in improving animal welfare is providing them with access to the outdoors. In this case, total space per animal will be even greater. Taking the example of laying hens again, the “free-range hens” label requires an outdoor area of 4 m² per hen. On a European scale, this would mean 1.2 billion m² for the 302 million hens that currently do not have access to the outdoors, or 120,000 hectares. For pigs, the Label Rouge plein air label requires 83 m² per pig, which, for the 22 million pigs raised for meat, would require 180,000 hectares. The same principle applies to rabbits, goats, chickens, etc., all of which uses space that could be used for other purposes, as discussed above.

Finally, outdoor access can have a negative impact on animal productivity. Outdoors, animals tend to exercise more, which expends energy and therefore requires more feed. In addition, although outdoor access limits the risk of infectious disease transmission due to lower animal density, it increases the risk of exposure to external pathogens and predators, as well as the risk of injury[33]. For example, in chickens, outdoor access can increase certain parasitic diseases such as coccidiosis or red mites.

Of course, outdoor access can be reduced to smaller areas and the spaces dedicated to this access can be designed to have a limited impact on the environment. However, limiting animal density will necessarily lead to an increased need for space. Compromises will therefore be needed.

Limiting excessive selection

A final argument in favor of animal welfare is to limit excessive selection based on production criteria and to promote the resilience and/or robustness of animals[34]. This involves, for example, limiting the hyper-prolificacy of sows or the rapid growth of chickens – which are detrimental to their welfare – by using less productive breeds or farming practices. As a consequence, production will take longer.

A Label Rouge chicken, for example, requires a minimum rearing period of 81 days, compared to the average 40 days for a “standard” chicken. This is twice as long and ultimately requires more space. The feed conversion ratio for a standard chicken in 2017 was around 1.67, compared to 3 for a Label Rouge chicken[35], which means that Label Rouge chickens need almost twice as much feed to produce the same amount of meat.

Promoting slow-growing animals allows for better animal development, improved welfare, and higher-quality meat, but this requires the use of more agricultural land and feed. Increased feed requirements have an impact on the environment, which is even more negative when the feed is not produced locally and must be imported, or when it involves deforestation[36]. Prioritizing local feed for animals and raising animals locally are therefore ways to limit the negative impact of these imports.

Conclusion

Due to all these constraints, improving animal welfare can lead to an increase in the carbon footprint of production, in CO₂eq of meat, milk, or eggs produced. Traditional environmental rating via life cycle assessments therefore favors the most intensive systems.

For example, a Shift Project report[37] states: « In laying hen farms, codes 3 (enriched cages), 2 (barn), 1 (free-range) and 0 (organic) respectively emit 1.66, 1.55, 3.34 and 2.57 kgCO2e/kg of eggs. Thus, a shift from code 3 to codes 1 and 0 with no change in livestock numbers would not lead to a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions “. Of course, the criterion of “greenhouse gas emissions” taken in isolation is too restrictive to judge the overall environmental performance of a system, its resilience and associated positive effects.

Furthermore, we have seen that improving animal welfare can also be a source of improvement in the environmental impact of livestock farming, whether through improved animal health or productivity, or through more virtuous farming systems.

The final calculation is not easy, and both aspects – animal welfare and environmental impact – must be improved together. The future of livestock farming cannot ignore either of these aspects, given their many interdependencies. Reconciling these two aspects requires compromises on the part of the authorities, the industry, and also citizens.

In any case, it seems necessary to reduce the number of animals raised and therefore individual meat consumption in order to limit the use and import/export of products that are most harmful to the environment, and to promote more extensive, robust farming practices that are more animal-friendly and have as little impact on the environment as possible. This will come at a cost to farmers, and everyone will have to agree to contribute.

In short

Thanks to Alain Ducos, lecturer and researcher at ENVT, for his contribution to writing this article and proofreading it!

[1] Courboulay V., Barbier B., Bellec T., et al., 2022. RHAPORC – Améliorer la relation homme animal en élevage porcin au bénéfice de l’homme et de ses animaux. Innovations Agronomiques 85, 323-334, https://doi.org/10.17180/ciag-2022-vol85-art25

[2] Waiblinger S., Menke C., Coleman G., 2002. The relationship between attitudes, personal characteristics and behavior of stockpeople and subsequent behavior and production of dairy cows. Applied Animal Behaviour Science 79 (3),195-219, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-1591(02)00155-7

[3] Hemsworth, P. H., & Barnett, J. L., 1991. The effects of aversively handling pigs, either individually or in groups, on their behaviour, growth and corticosteroids. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 30(1-2), 61-72. https://doi.org/10.1016/0168-1591(91)90085-C

[4] Breuer, K., Hemsworth, P. H., Barnett, J. L., Matthews, L. R., & Coleman, G. J., 2000. Behavioural response to humans and the productivity of commercial dairy cows. Applied animal behaviour science, 66(4), 273-288. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-1591(99)00097-0

[5] Robichaud, M. V., Rushen, J., De Passillé, A. M., Vasseur, E., Orsel, K., & Pellerin, D., 2019. Associations between on-farm animal welfare indicators and productivity and profitability on Canadian dairies: I. On freestall farms. Journal of Dairy Science, 102(5), 4341-4351. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-1591(99)00097-0

[6] Terlouw, E. M. C., Cassar-Malek, I., Picard, B., Bourguet, C., Deiss, V., Arnould, C., … & Lebret, B., 2015. Stress en élevage et à l’abattage: impacts sur les qualités des viandes. INRAE Productions Animales, 28(2), 169-182. https://doi.org/10.20870/productions-animales.2015.28.2.3023

[7] Krug, C., Haskell, M. J., Nunes, T., & Stilwell, G. (2015). Creating a model to detect dairy cattle farms with poor welfare using a national database. Preventive veterinary medicine, 122(3), 280-286. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prevetmed.2015.10.014

[8] Green, L. E., Kaler, J., Wassink, G. J., King, E. M., & Thomas, R. G. (2012). Impact of rapid treatment of sheep lame with footrot on welfare and economics and farmer attitudes to lameness in sheep. Animal Welfare, 21(S1), 65-71. doi:10.7120/096272812X13345905673728

[9] Skuce et al., 2022, Acting on methane: opportunities for the UK cattle and sheep sectors. Moredun Research Institute.

[10] Rodrigues da Costa, M., & Diana, A. (2022). A systematic review on the link between animal welfare and antimicrobial use in captive animals. Animals, 12(8), 1025. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12081025

[11] McKellar Q. A., Ecotoxicology and residues of anthelmintic compounds. Veterinary Parasitology, 1997;72:413-415, cité par Jacquiet et al (2024) https://doi.org/10.1051/npvelsa/2024010

[12] See our article: Farm animals are given feed containing antibiotics: TRUE or FALSE?

[13] Le Cozler, Y. (2015). Reproduction chez la génisse laitière. Repromag, 2015, 12-23. hal-01210956

[14] See our article: Breeding practices: extended lactation in goats

[15] Michaud, A., Plantureux, S., Baumont, R., & Delaby, L., 2020. Les prairies, une richesse et un support d’innovation pour des élevages de ruminants plus durables et acceptables. INRAE Productions Animales, 33(3), 153-172. https://doi.org/10.20870/productions-animales.2020.33.3.4543

[16] Bareille, N., Haurat, M., Delaby, L., Michel, L., & Guatteo, R. (2019). Quels sont les avantages et risques du pâturage vis-à-vis de la santé des bovins. Fourrages, 238, 125-131. hal-02626493

[17] Grazing can also have a negative impact on animal welfare, particularly if they do not have shelter to protect them from wet weather or extreme heat, if access to sufficient quantities of good-quality water is not guaranteed, or if their feed ration is not sufficiently balanced. In addition, grazing exposes animals to greater risk of predation and parasitism, which can lead to the transmission of various diseases. See our article « Grazing animals are necessarily happy, TRUE OR FALSE? »

[18] Mach, N., Lansade, L., Bars-Cortina, D., Dhorne-Pollet, S., Foury, A., Moisan, M. P., & Ruet, A. (2021). Gut microbiota resilience in horse athletes following holidays out to pasture. Scientific reports, 11(1), 5007. 10.1038/s41598-021-84497-y

[19] The carbon storage capacity of grasslands varies depending on time and good practices such as limiting land use change and protecting permanent grasslands, practicing rotational grazing, limiting stocking rates, and amending the soil with manure while limiting tillage and excessive fertilization. See our article « Grasslands help offset part of cows’ greenhouse gas emissions, TRUE or FALSE? »

[20] Dumont, B., Farruggia, A., Garel, J. P., Bachelard, P., Boitier, E., & Frain, M. (2009). How does grazing intensity influence the diversity of plants and insects in a species‐rich upland grassland on basalt soils?. Grass and Forage Science, 64(1), 92-105. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2494.2008.00674.x

[21] When their concentration is too high, effluents can acidify soils, cause eutrophication of waterways, and lead to a loss of biodiversity.

[22] See our article: Is it a good idea to put horses and cows in the same pasture?

[23] See our article: Hedgerows are essential for the welfare of free-range animals, TRUE or FALSE?

[24] EFSA AHAW Panel (EFSA Panel on Animal Health and Animal Welfare), Nielsen SS, Alvarez J, Bicout DJ, Calistri P, Canali E, Drewe JA, Garin-Bastuji B, Gonzales Rojas JL, Schmidt CG, Herskin M, Michel V, Miranda Chueca MA, Padalino B, Pasquali P, Roberts HC, Spoolder H, Stahl K, Velarde A, Viltrop A, Jensen MB, Waiblinger S, Candiani D, Lima E, Mosbach-Schulz O, Van der Stede Y, Vitali M and Winckler C, 2023. Scientific Opinion on the welfare of calves. EFSA Journal 2023; 21(3):7896, 197 pp. https://doi.org/10.2903/j.efsa.2023.7896

[25] Euroopean data on laying hens

[26] Increasing the surface area of buildings will have consequences in terms of resource use, such as metals and concrete, with the negative impacts that mining and sand extraction have on global warming, pollution, and the destruction of natural habitats.

[27]Agreste – Mémento 2023 France

[28] Green, R. E., Cornell, S. J., Scharlemann, J. P., & Balmford, A. (2005). Farming and the fate of wild nature. science, 307(5709), 550-555. doi: 10.112

[29] Synthèse bibliographique du CNR BEA sur les impacts des sols pleins partiels ou totaux sur le bien-être et le comportement des porcs

[30] Welfarm – DES PORCS, DES ÉLEVAGES, DES LITIÈRES : Des éleveurs témoignent

[31] Agreste – Synthèses conjoncturelles : porcins

[32] Synthèse bibliographique du CNR BEA sur les impacts des sols pleins partiels ou totaux sur le bien-être et le comportement des porcs

[33] Agreste – Production de paille en France

[34] Ducrot, C., Barrio, M. B., Boissy, A., Charrier, F., Even, S., Mormède, P., … & Fernandez, X., 2024. Améliorer conjointement la santé et le bien-être des animaux dans la transition des systèmes d’élevage vers la durabilité. INRAE Productions Animales, 37(3), 8149-8149. https://doi.org/10.20870/productions-animales.2024.37.3.8149

[35] Friggens, N. C., Blanc, F., Berry, D. P., & Puillet, L. (2017). Deciphering animal robustness. A synthesis to facilitate its use in livestock breeding and management. Animal, 11(12), 2237-2251. https://doi.org/10.1017/S175173111700088X

[36] ITAVI – Performances techniques et coûts de production

[37] The Shift Project – Pour une agriculture bas carbone, résiliente et prospère

Keep in mind

- Improving animal welfare improves their productivity: fewer animals are needed to produce the same amount of meat, milk, eggs, etc., which limits the negative impacts of livestock farming.

- Improving animal health reduces the use of drugs and lowers their environmental impact.

- Some farming practices, such as grazing, are beneficial for animals and the environment.

- Increased space, bedding, and outdoor access are essential for animal welfare but have an impact on the environment.

Key Figure

Number of additional hectares required to provide outdoor access for pigs raised for meat in France.