No, not exactly!

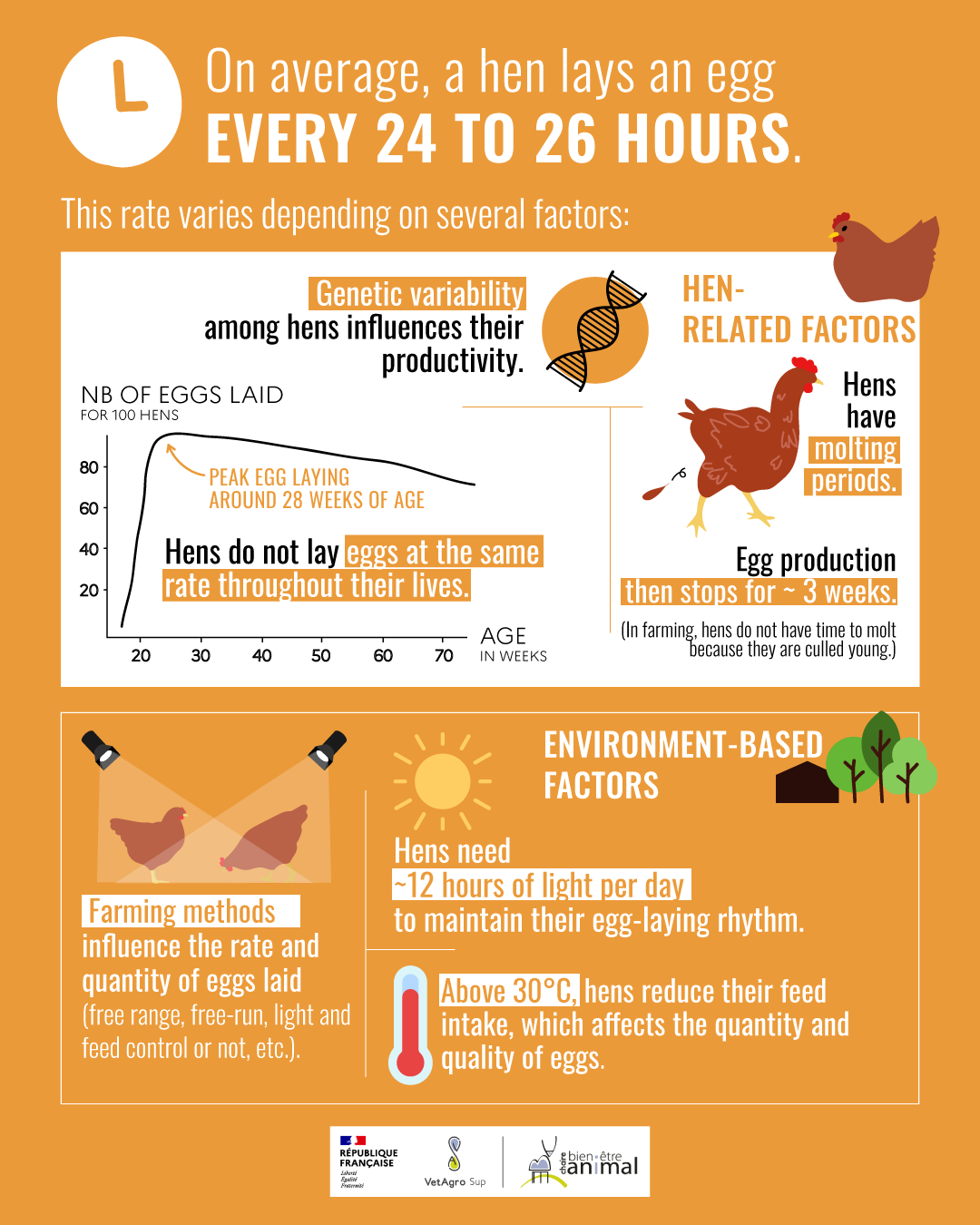

On average, a hen lays an egg every 24 to 26 hours, taking breaks from time to time. This laying rhythm is never perfectly constant: it varies according to a hen's genetics, evolves throughout its life, and is influenced by environmental factors. To maintain regular production, a hen needs at least 12 hours of light per day and a temperature below 30°C (86°F). This is why egg laying naturally slows as days shorten (from autumn onward, reaching a minimum in winter) or during periods of high temperatures.

Keep in mind

- At peak laying, hens lay one egg every 24 to 26 hours.

- In order to lay eggs, hens need at least 12 hours of light per day and an ambient temperature below 30°C.

- In farming, hens generally lay between 280 and 320 eggs per year and often have short careers.

Production and consumption

Egg production and consumption in France

Production

57 million hens are raised for their eggs in France, making France one of the largest egg-producing countries in the European Union. In 2023, the French laying-hen sector produced 99% of the eggs consumed in France[1]. However, the sector remains vulnerable to risks: avian influenza, for example, led to a decrease in egg production in France in 2022[2]. France is not the only country affected: in the United States, the avian influenza epidemic that began in 2022 has already affected more than 170 million poultry (infected or culled as a precautionary measure)[3], mainly laying hens, between February 2022 and January 2025. This has led to a significant decrease in the supply of eggs and a sharp increase in the average price of eggs in early 2025.

In recent years, the laying hen sector has undertaken the conversion of enriched cage systems to alternative systems (free-run, free-range, and organic) to meet the commitments of major retailers and numerous operators who, faced with societal demand, have decided to stop marketing shell eggs from enriched cage systems (code 3) by the end of 2025[4]. If the number of poultry houses remains unchanged and they are not expanded, this conversion will lead to a reduction in housing capacity, with an estimated loss of 2.5 to 3 million places (each place representing the space needed for one hen) in France. Indeed, in enriched cage systems, each hen must have a minimum of 750 cm², compared to approximately 1,000 cm² per hen in free-run or free-range systems. Switching from caged farming to floor or free-range farming therefore reduces the number of hens per building.

Consumption

In 2023, the average French person consumed 224 eggs annually, 24 more than in 2013[5]. This represents slightly more than four eggs per week. This includes shell eggs as well as processed eggs present in food products (egg products). Egg products accounted for 41% of annual egg consumption in 2023, or approximately 92 eggs per person in France.

While egg production and consumption in France are closely linked to consumer choices, farming methods, and the number of hens in production, they depend above all on one central element: the laying hen itself. It is its biological rhythm that determines, egg after egg, the volume of production. Understanding the mechanisms of egg formation therefore allows for a better grasp of the challenges and limitations of the industry.

Domestication and the role of egg laying

Domestication of chicken began several thousand years ago from the European Red Junglefowl (G. gallus spadiceus), a species of Phasianidae native to Southeast Asia. In this wild ancestor, the natural reproductive cycle is limited to a single clutch per year, consisting of fewer than six eggs.

The domestic chicken (G. gallus domesticus), on the other hand, can lay eggs all year round. This ability is the first recorded evidence of the disappearance of seasonal laying[6], the result of the selection carried out by humans over time based on this trait.

Furthermore, egg production does not necessarily involve a rooster: hens can lay eggs on their own. Without fertilization, the eggs produced will not hatch into chicks[7]. It is these unfertilized eggs that are used for consumption.

Egg formation

Egg formation

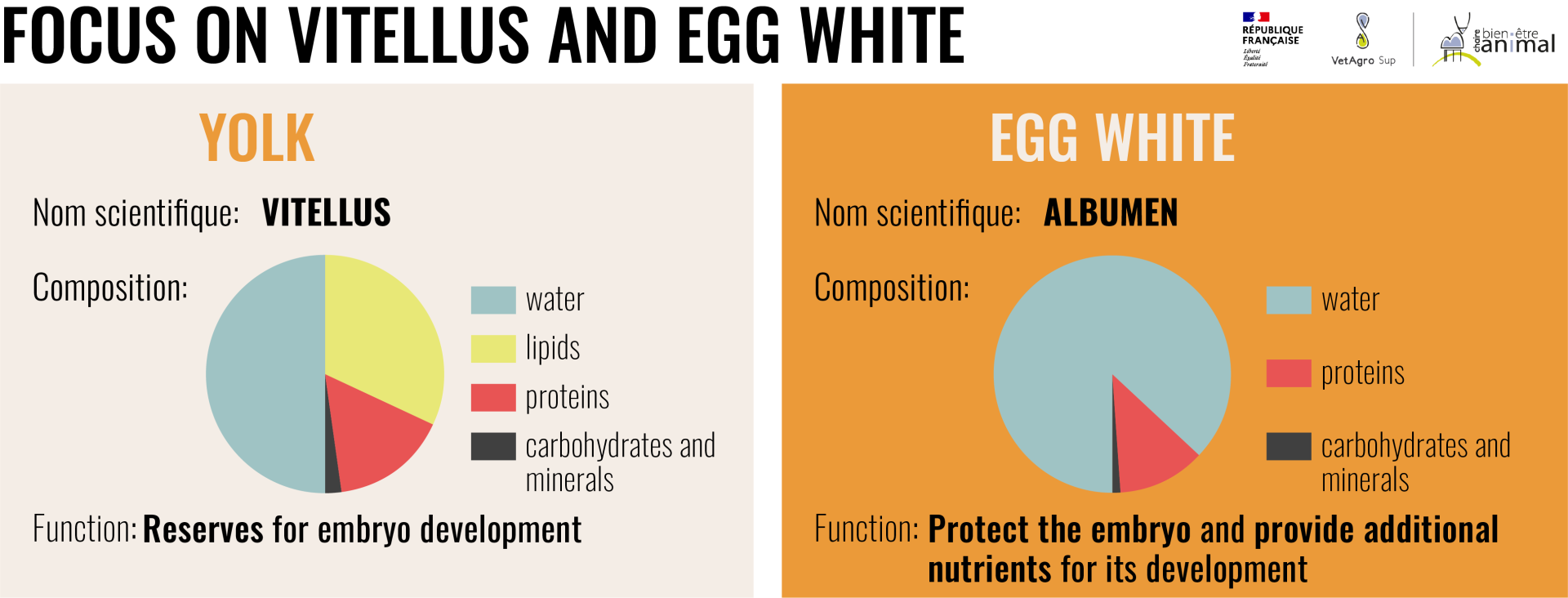

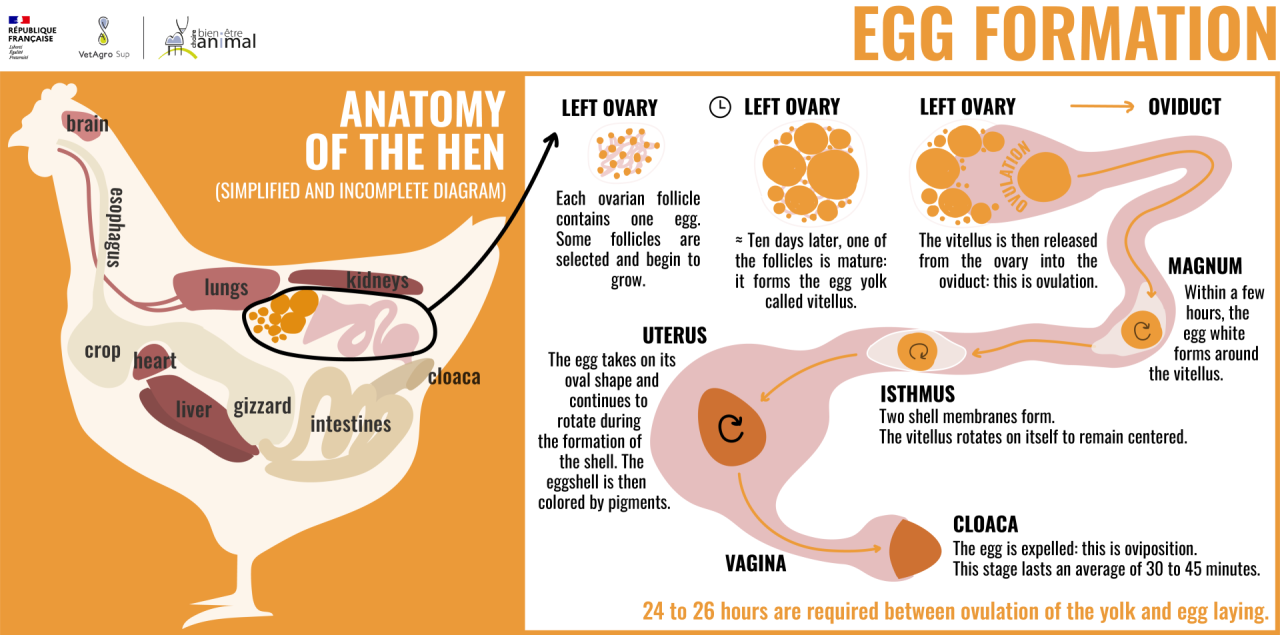

Adult hens have several thousand ovarian follicles, each containing one egg. These follicles develop only in the hen’s left ovary, which is the only functional one! The right ovary is non-functional in all hens. In the left ovary, follicles begin to grow, forming the yolk, also known as the vitellus, in about ten days. Once mature, the vitellus is released from the ovary into the oviduct (ovulation), a tube approximately 65 cm long where the egg will continue to develop.

Within a few hours, in the part of the oviduct called the magnum, the egg white (albumen) forms around the vitellus, which rotates on itself in order to remain centered.

The egg then continues its journey through the oviduct and reaches a new section, the isthmus, where two shell membranes are formed from calcium carbonate.

Once in the uterus, the egg takes on its oval shape and continues to rotate, allowing the shell to form evenly. Still in the uterus, the eggshell is colored by pigments.

Once all these steps are completed, the egg is expelled through the last part of the oviduct, the cloaca: this is oviposition. This stage lasts on average 30 to 45 minutes, depending on the breed[8], during which the hen remains on the nest.

24 to 26 hours are required between ovulation of the yolk and egg laying[9].

Did you know?

In France, brown eggs are the most commonly consumed, while in the United States, white eggs are predominant. This difference is related to chicken breed: in France, farms mainly raise red hens, such as the Rode Island Red, which lay brown eggs. In the United States, breeds like the White Leghorn, with white plumage, are preferred, as they lay white-shelled eggs.

Egg-laying behavior

Egg-laying behavior

Building a nest is an essential behavioral need for hens. Before laying eggs, they exhibit this behavior by scratching the ground or litter, turning over in the nest, and, if possible, collecting bedding to furnish it. For the nest to be used, it must be well located, and have an attractive color, lighting,and flooring. If these conditions are not met, hens may lay outside the nest, and the eggs must be collected manually by the breeder, which is an additional workload.

An egg laid outside the nest is an egg whose laying date is unknown. It is therefore automatically downgraded as unfit for human consumption. It can be used for other purposes, such as animal feed. In addition, these eggs are often soiled, broken, or eaten by the hens, which makes them unmarketable, resulting in a loss for the breeder[10],[11].

Factors influencing egg laying

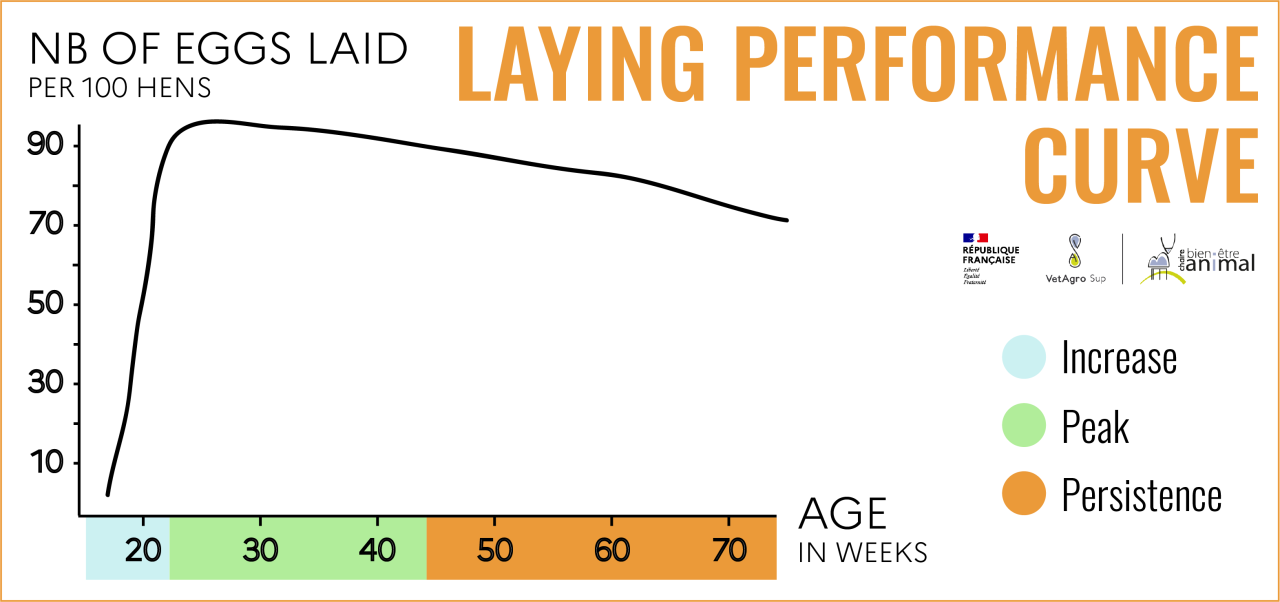

In hens, ovulation can occur almost daily, allowing for the laying of one egg per day for several consecutive days. This is known as a “clutch”. Clutches are interspersed with “pauses”, or days without egg production. A clutch lasts around ten days on average. However, modern laying hens, highly specialized for egg production, can achieve clutches of over 100 days[12].

During the life of a hen

Hens generally start laying eggs at around 17 to 18 weeks of age, after reaching puberty. They then reach their peak laying age at around 28 weeks, during which time their egg production is at its highest. At their peak, hens will lay eggs around 9 days out of 10. From 44 weeks onwards, egg production gradually begins to decline: this phase is called “persistency”, where hens continue to lay eggs until around 75 to 76 weeks (i.e., up to around a year and a half), at which age they are often sent to slaughter or sometimes adopted by private individuals[13].

Did you know?

A so-called “spent” laying hen is over 18 months old, and generally destined for slaughter. It can sometimes be adopted by individuals. Although it continues to lay eggs, its laying rate is lower than production requirements.

In private homes, a hen’s lifespan can reach 12 years. However, egg production gradually decreases from the age of 3, then comes to a stop around 6 to 8 years, depending on the breed.

Throughout the year

Hens need approximately 12 hours of light per day to keep their laying rhythm. In autumn and winter, since days are shorter, egg production naturally decreases. Similarly, in hot weather, above 30°C, hens reduce their feed intake, affecting both the quantity and quality of production.

Once they reach adulthood (from 18 months of age), hens may enter a molting period, a natural phenomenon during which they renew part of their plumage. During molting, egg production stops for about 3 weeks. Once molting is over, egg laying resumes and the number of eggs laid per hen is increased compared to the pre-molting period[14]. This phenomenon is “invisible” in laying hen farms, due to the young age of hens.

🐔 Focus on the molting of hens

Moulting is the period when hens naturally lose and renew their feathers. This phenomenon, which is completely normal in birds, is usually accompanied by a temporary halt in egg-laying.

In nature, moulting generally occurs in autumn, after the breeding and incubation period and before migration in wild birds. In farms outside the European Union[15], it can be triggered deliberately to allow hens to ‘take a break’, but this involves drastically reducing their feed and access to water. This allows them to regain energy, improve their performance and produce better quality eggs for a new laying cycle.

Influence of genetics

Another factor that determines egg production is genetics. The naturally occurring genetic variability among hens has been used to select the most productive individuals. This selection has led to the development of particularly high-performing commercial breeds, now capable of laying more than 300 eggs per year. The Isa Brown, for example, is one such breed.

Selection focuses in particular on age at puberty: the younger the pullets (young hens that have not yet reached sexual maturity) are when they reach puberty, the earlier they begin laying eggs. Another criterion concerns laying persistence, that is, the hens’ ability to maintain high egg production over a prolonged period. Extending laying careers would allow for a reduction in the total number of animals raised while maintaining the level of production [16].

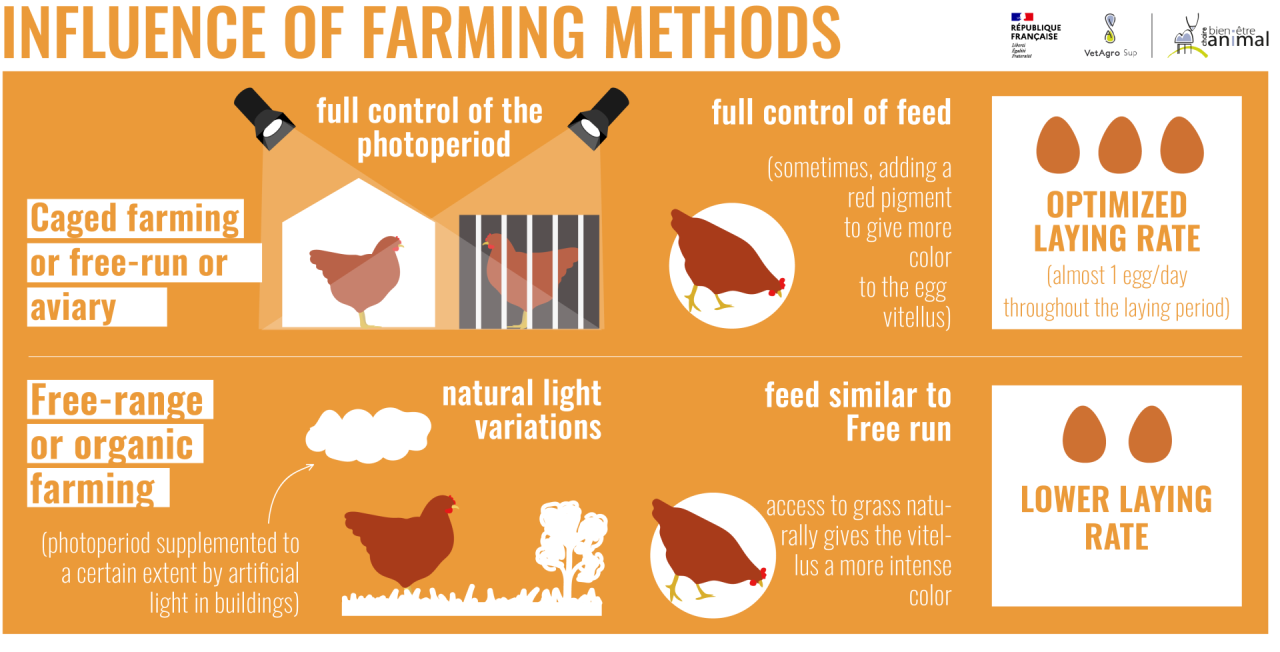

Influence of livestock farming systems

Farming methods influence the rate and quantity of eggs laid. In indoor settings, optimized conditions (feed, artificial light, selective breeding) allow hens to maintain a laying rate of almost one egg per day throughout the entire productive phase. To keep hens productive, a stable photoperiod of 14 to 16 hours of light per day is maintained in the buildings.

Regardless of the photoperiod, the moment light (natural or artificial) disappears automatically “triggers” ovulation. Ovulation will occur approximately 6 hours after the lights go out. In enclosed buildings, it is therefore possible to use this physiological effect to shift egg laying throughout the day by changing the lighting period, and thus the timing of ovulation in hens. This can be used to change the egg collection period.

In extensive farming systems, particularly free-range systems, natural variations in daylight do not allow the same high laying rates as in fully indoor systems. Organic farming standards allow natural light to be supplemented with artificial lighting, up to a maximum of 16 hours of light per day, provided that hens are given a continuous nighttime rest period of at least 8 hours without artificial light.

The composition of an egg depends primarily on the hens’ diet, not on the farming system. Thus, the positive image of “free-range” eggs among consumers rests more on a positive perception of the farming method than on any real nutritional or qualitative differences. The color of the yolk, linked to carotenoid intake, is generally more intense in hens with access to an outdoor range, even if their diet is identical, than in those raised in enriched cages. However, eggs from conventional farms can also appear more colored due to the addition of red pigments to the feed[17].

Conclusion

A hen’s laying rate, although averaging one egg every 24 to 26 hours, varies depending on numerous biological and environmental factors. These include a hen’s genetics, age, total daytime, and room temperature. Environmental factors impact its physiology and its ability to produce eggs.

In poultry farming, to maintain production, these variations can be partially controlled. Laying hens are selected to start laying early, often have short careers, and are culled young, after only one laying cycle, to avoid the natural decline in performance associated with age. Ultimately, in poultry farming, a hen lays between 280 and 320 eggs per year.

However, although these practices optimize yield while meeting market demands, they also raise questions regarding the balance between animal welfare, economic profitability and farming systems sustainability.

In summary

[1] See also our species sheet!

[2] Influenza aviaire : la situation en France

[3] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) – H5 Bird Flu: Current Situation

[4] Caractéristiques et avenir du parc bâtiment pondeuses en cages – ITAVI

[5] Dossier de presse juin 2024 – CNPO

[6] Peters, C., Richter, K. K., Wilkin, S., Stark, S., Mir-Makhamad, B., Fernandes, R., … & Spengler III, R. N. (2024). Archaeological and molecular evidence for ancient chickens in Central Asia. Nature communications, 15(1), 2697.

[7] See also A rooster needed for a hen to lay eggs! TRUE or FALSE?

[8] Bécot, L., Bédère, N., & Pascale, L. E. (2021). Sélection sur la ponte des poules en systèmes alternatifs à la cage. INRAE Productions Animales, 34(1), 1-14.

[9] Sauveur, B. (1988). Reproduction des volailles et production d’oeufs. Quae.

[10] Bécot, L. (2023). Sélectionner des poules pondeuses adaptées à des systèmes d’élevage alternatifs à la cage (Doctoral dissertation, Agrocampus Ouest).

[11] Michel, V., Arnould, C., Mirabito, L., & Guémené, D. (2007). Systèmes de production et bien-être en élevage de poules pondeuses. INRAE Productions Animales, 20(1), 47-52.

[12] Bécot, L., Bédère, N., & Pascale, L. E. (2021). Sélection sur la ponte des poules en systèmes alternatifs à la cage:(Full text available in English). INRAE Productions Animales, 34(1), 1-14.

[13] Bécot, L. (2023). Sélectionner des poules pondeuses adaptées à des systèmes d’élevage alternatifs à la cage (Doctoral dissertation, Agrocampus Ouest).

[14] Travel, A., Nys, Y., & Lopes, E. (2010). Facteurs physiologiques et environnementaux influençant la production et la qualité de l’œuf. INRAE Productions Animales, 23(2), 155-166.

[15] European Commission – Overview report Protection of the welfare of laying hens at all stages of production

[16] Bécot, L. (2023). Sélectionner des poules pondeuses adaptées à des systèmes d’élevage alternatifs à la cage (Doctoral dissertation, Agrocampus Ouest).

[17] Travel, A., Nys, Y., & Lopes, E. (2010). Facteurs physiologiques et environnementaux influençant la production et la qualité de l’œuf. INRAE Productions Animales, 23(2), 155-166.

Keep in mind

- At peak laying, hens lay one egg every 24 to 26 hours.

- In order to lay eggs, hens need at least 12 hours of light per day and an ambient temperature below 30°C.

- In farming, hens generally lay between 280 and 320 eggs per year and often have short careers.

Key Figure

Temps entre chaque ponte d’une poule