IT DOES!

In many ways, grass, cattle, and horses go hand in hand! In many ways, cattle and horses are a perfect match when it comes to grazing! Not only do cows and horses graze differently, but they also don't pick the same plant species. This diet complementarity has benefits for them as well as for the environment, particularly in terms of biodiversity and the use of antiparasitic treatments. However, further research is needed to determine the optimal management of mixed equine-cattle grazing.

Keep in mind

- The feed choices of grazing cattle and horses are complementary.

- Mixed grazing can promote: grass utilization, biodiversity of flora and fauna, dilution of parasite load, and human-animal interactions.

- Grazing helps to limit: the purchase of feed, the work involved in maintaining pastures, the administration of dewormers, and antibiotic resistance.

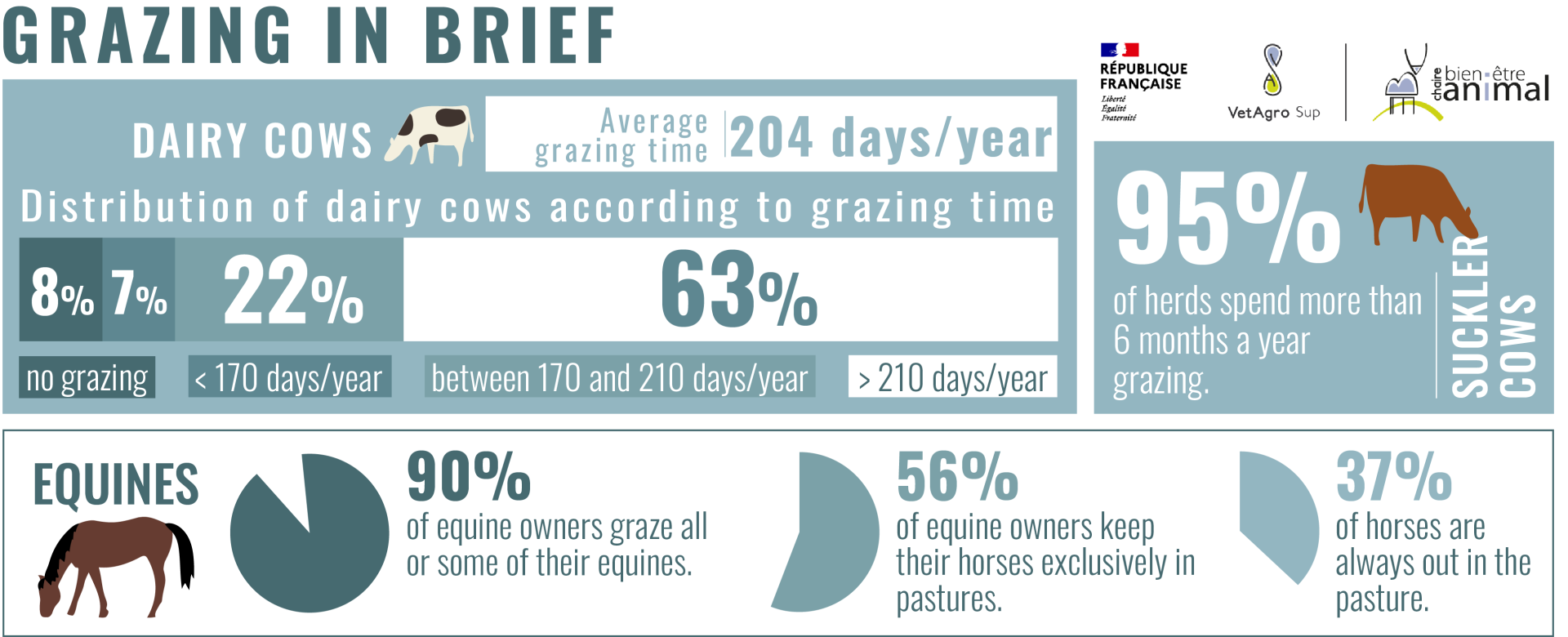

The French livestock population numbers approximately 17 million cattle[1] and 1 million equines[2]. Both these large herbivores play an important role in maintaining grasslands. In grassland regions, it is not uncommon to see them grazing together in the same paddock: this is known as mixed grazing. What are the benefits of such a combination for cattle and equines? What are the impacts on local flora and fauna?

About grazing

A few reminders about grazing

The floral composition of meadows

In France, the specific floral diversity of permanent grassland, including all plants, varies between 10 and 40 different species[7].

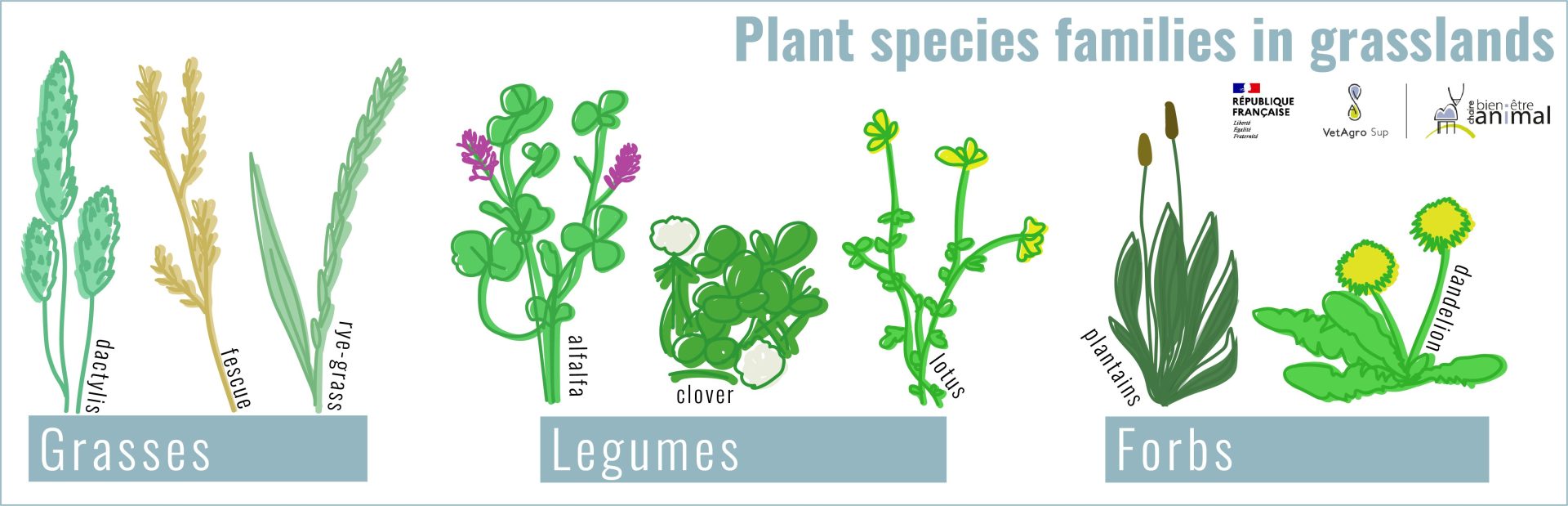

Three main families of plant species are present in grasslands[8][9] :

- Grasses (or Poaceae): the basis of the grassland vegetation cover. Grasses account for 3/4 of the plant species in permanent grasslands[10]. They are monocotyledons (monocots), and provide animals with dry matter and energy.

- Legumes (or Fabaceae): they fix atmospheric nitrogen and transform it into organic nitrogen usable by nearby plants, hence the name “Green manures”. They are dicotyledons (dicots). Legumes are an important source of plant protein (nitrogenous matter) for animals. Because they are more heat-resistant than grasses and grow quickly, legumes can become dominant in cases of overgrazing or drought.

- Forbs: these are neither grasses nor legumes, although most are dicots. Some are wrongly called “weeds.” Forbs are an important source of minerals and vitamins and are particularly more drought-resistant than grasses.

The impact of herbivores on the floral diversity of grasslands

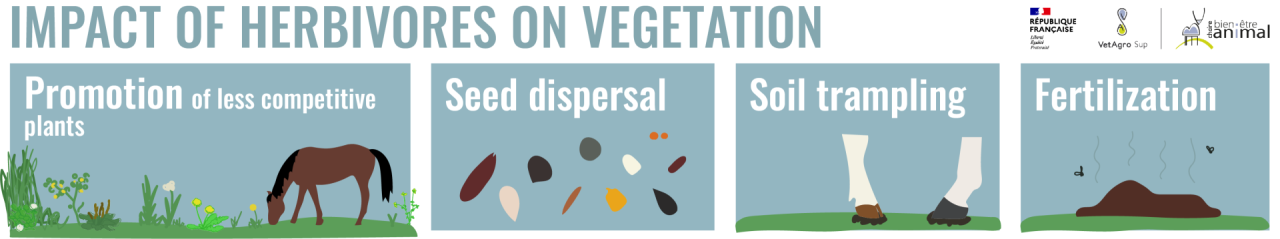

During grazing, herbivores act on vegetation through several mechanisms:

- The expression of food preferences: herbivores pick plants in a more or less selective way, thus creating openings in the environment, conducive to the proliferation of other plants, less competitive for light or nutrients;

- The dispersal of certain plants’ seeds, via their hairs, hooves or excrement;

- Soil trampling;

- The supply of nutrients, via the spreading of urine and feces, which contribute to plant growth.

All of these factors create contrasting environmental conditions that allow for greater coexistence of plant species in grazed plots compared with ungrazed plots. Indeed, in ungrazed meadows, homogeneous fertilization and mowing – which consists of cutting all the species present indiscriminately – tend to homogenize the plant cover[11][12].

Feeding behavior

Two herbivores with different feeding behaviors

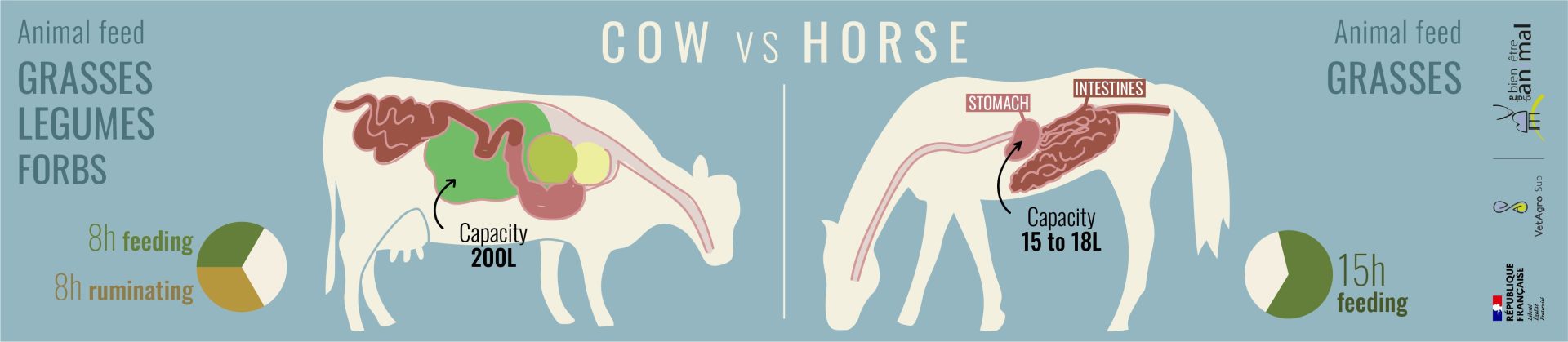

Cattle and horses have a similar diet: they are herbivores with a strong preference for grasses[13]. But while they have much in common, they are distinguished by their digestive systems. The first differences can be seen in their mouth’s anatomy.

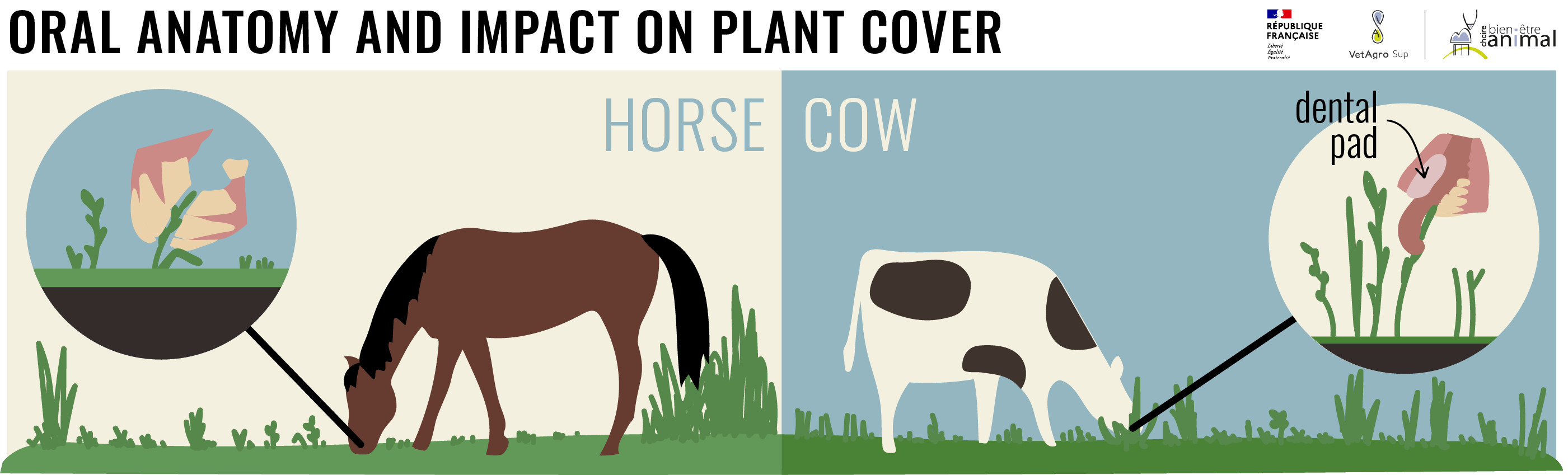

Oral anatomy and its impact on vegetation cover structure

Although both species are herbivores, horses and cattle do not have the same anatomical ‘equipment’ for grasping standing grass.

The horse has incisors on both jaws, which allows it to graze close to the ground, cutting the grass very near the ground (1 to 2 cm)[14]. It therefore prefers to graze in short areas where it keeps the grass at an early stage of development (high nutritional value) and avoids tall areas, known as “refusal zones”, where it concentrates its droppings.

The cow, on the other hand, lacks incisors in its upper jaw. Instead, its gums are more prominent, forming what is called the dental pad. To cut grass, the cow therefore uses its tongue to grasp a clump of grass, which it pinches between its lower incisors and the dental pad. This grasping technique does not allow cattle to exploit young, short grass, which they are unable to seize. They prefer intermediate to tall sward heights, which they cut at 5 cm or more[15].

Digestive physiology and its impact on plant species selection

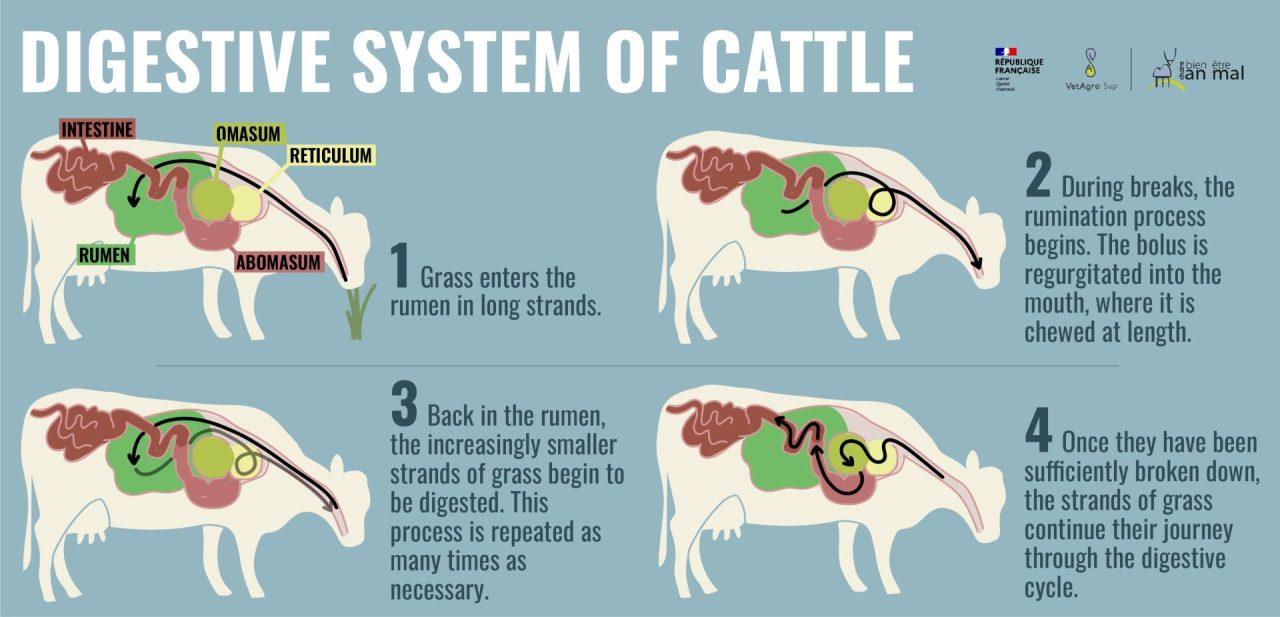

Although cows have fewer teeth than horses, they do have more… “stomachs”! This anatomical specificity induces a different digestive process, which impacts the consumption of grassland species.

Cattle are polygastric animals, meaning their stomach (the abomasum) is preceded by three pre-stomachs (the rumen, the reticulum, and the omasum). During grazing, the cow swallows the ingested grass quickly and chews it very little: the grass thus reaches the rumen in the form of long strands.

During breaks from feeding, the cow, usually lying down, begins its rumination process. The food bolus is then regurgitated, returning from the rumen to the oral cavity, where it is mixed with a large amount of saliva and thoroughly chewed to reduce particle size and make it more digestible. Back in the rumen, the increasingly smaller strands of grass begin to be digested by the microorganisms of the gut flora through fermentation. This process is repeated as many times as necessary. Every day, a cow spends 8 hours eating and 8 hours ruminating![15][16]

When it is sufficiently crushed, grass then continue its journey into the next compartments. In total, it takes one blade of grass between two and three days to be entirely digested![17]

Did you know?

Of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from livestock farming, 62% are attributed to cattle. This is due to their total biomass, which is significantly greater than that of other livestock, and also to their specific digestive process, which results in methane emissions (through rumination). However, grasslands help to partially offset these GHG emissions by contributing to carbon sequestration. This is especially true for grazed grasslands.

To find out more, see our dedicated article: Grasslands help offset part of cows’ greenhouse gas emissions, TRUE or FALSE?

Though it may look constraining, this digestive process offers several advantages. Firstly, the longer the forage particles stay in the digestive system, the more efficient the digestion of grass. Secondly, the rumination process reduces the risk of poisoning, notably by allowing the detoxification of secondary metabolites that may be present in legumes and flowering plants, such as tannins[18]. This allows cattle to consume a wide range of plant species, resulting in a fairly homogenous use of the vegetation cover.

The horse, however, is not a ruminant. It has a single, small stomach that constantly produces acidic gastric secretions. This means that it must continuously ingest small amounts of forage. In natural conditions, the horse spends an average of 15 hours a day feeding[19].

Did you know?

The volume of a horse's stomach varies between 15 and 18 L, whereas a cow's rumen alone can reach 200 L!

Due to the absence of a rumen, the horse’s digestive efficiency is lower than that of the cow. The horse compensates for this with a high feed intake: the amount of grass ingested by grazing horses is estimated to be 63% higher than that of cattle[15]. Thanks to this ability to eat more, horses ultimately absorb more nutrients from forage than cattle![20]

At the same stocking rate[21], horses ensure a more drastic cutting of vegetation, allowing open environments to be better maintained than with cattle.

However, because horses have no rumen, they are unable to detoxify the secondary metabolites found in many dicots. As a result, horses are more selective than cattle: they tend to avoid – and therefore preserve – legumes and forbs, feeding primarily on grasses.

In summary, horse grazing is characterized by the selective consumption of very large quantities of grasses and the creation of a mosaic of short and tall vegetation. The open environment and the resulting structural heterogeneity of the plant cover promote significant biodiversity. The diversity of plant cover is thus greater in pastures grazed by horses compared to pastures grazed by ruminants[22][23][24]. However, it should be noted that those benefits are directly dependent on pasture management practices: if ill-adapted (excessive stocking rates, excessive grazing time, etc.), horse grazing alone can lead to overgrazing and the expansion of “refusal zones”, which can eventually account for 30 to 50% of the pasture area.

In short

The grazing methods of cattle and horses have similarities (strong appetite for grasses), but also differences: while cattle use the plant cover in a rather homogeneous way, horse grazing promotes better floral diversity while also having “refusal zones”, which are not grazed.

Is it possible to take advantage of the specific characteristics of both species by combining them on the same plot? Are they complementary?

Impacts of mixed cattle/horse grazing

Mixed grazing is the association of herbivores of different species (cattle-horse, sheep-cattle, etc.) on the same pasture, simultaneously or successively during a grazing season, with the aim of optimizing the use of plant resources.

Through compensatory mechanisms between the grazing patterns of different herbivore species, mixed grazing can impact vegetation cover in a way that differs from monospecific grazing. Is this the case with mixed cattle/horse grazing?

On the use of plant cover

When stocking rates are balanced, mixed grazing encourages horses to graze on the bare areas cattle do not value and, conversely, encourages cattle to eat the tall areas that horses leave untouched. The complementary nature of the species thus limits areas of uneaten forage and promotes the maintenance of open spaces. By minimizing uneaten forage, the complementary use of different plant families by horses and cattle allows them to consume a larger share of the pasture’s grass.

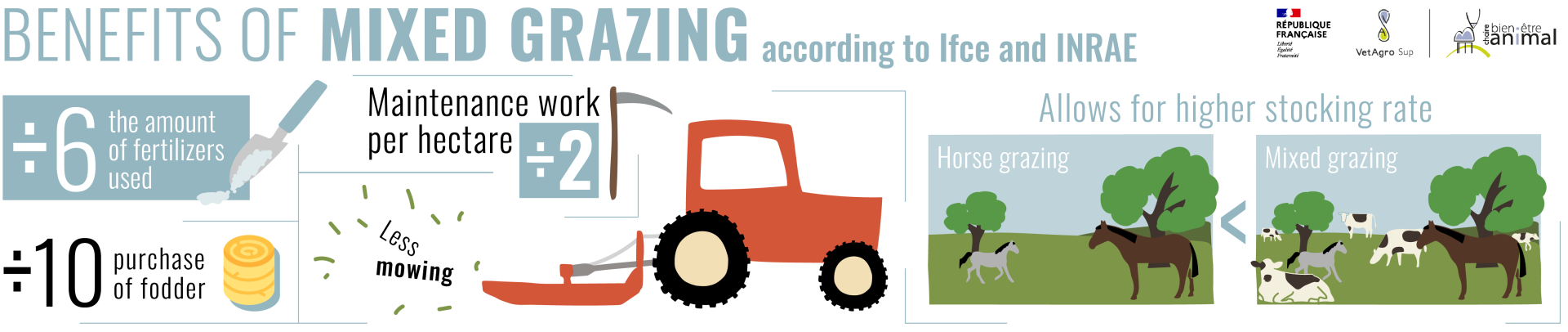

Within the framework of the EquiBov research project, jointly led by IFCE and INRAE, surveys were conducted on mixed cattle-horse farms and specialized horse farms in the Massif Central region. They highlighted the following points[25] :

- Mixed grazing allows for a higher stocking rate compared to horse grazing alone.

- The quantity of fodder purchased per LSU[26] is 10 times lower in mixed farms.

- The use of mineral fertilizers is 6 times lower in mixed farms.

- Mixed farms make less frequent use of the ground mulcher.

- Seasonal maintenance work per hectare (mowing, harvesting, hedge trimming, etc.) is reduced by half in mixed systems.

It should be noted, however, that there is considerable variability in how the two species are managed in mixed grazing systems: the presence of cattle and horses can be simultaneous or successive; in the latter case, the order in which they graze may vary (cattle then horses or horses then cattle); the duration of the rotation between plots may fluctuate; as may the cattle-to-horse ratio.

Regarding this last point, the optimal ratio may sit around 70/30% of live weight, or 1 horse for every 3 cattle. This proportion appears ideal for limiting the presence of refusal zones while preserving the individual performance (daily live weight gain – in other words, growth) of both cattle and horses, thus limiting the purchase of supplementary feed[27].

On biodiversity

As noted before, horse grazing promotes plant diversity. In the long term, however, the density in upland, ungrazed areas generates competition for light. Stimulated by the nitrogen in manure, nitrophilic species[28] accumulate and, being larger, slow down or even prevent the development of other species, thus reducing biodiversity. Cattle grazing therefore acts in a complementary way by limiting the development of these competitive nitrophilic species in upland areas abandoned by horses[29].

Conversely, horses enjoy short grass which cannot be eaten by cattle… a mutually beneficial exchange!

Thus, at moderate stocking rates (750kg live weight per hectare, i.e. about one heifer and one mare per hectare), various studies have shown that mixed equine-bovine grazing improves biodiversity compared to separate grazing[29].

But the positive effects of grazing on biodiversity are not limited to plants! Indeed, herbivores play an important role in maintaining faunal diversity within grazed environments. It has been shown that mixed grazing promotes the presence of pollinating insects, the diversity of resources for herbivorous and granivorous wildlife, and the accessibility of prey for birds that require open habitats[30]. To achieve this, it is important not to graze a plot continuously, nor to have an excessive stocking rate, which would prevent flowering.

On parasitism

Mixed grazing also helps to reduce the level of parasitic infestation in animals.

Indeed, horses and cattle only have two parasites in common: Trichostrongylus axei, a strongyle, and the large liver fluke (Fasciola (hepatica). Other gastrointestinal parasites found in horses and cattle exhibit strong host specificity. Thus, when the larva of an equine parasite is ingested by a bovine, it will not be able to complete its development and lay its eggs in this other host’s body. And vice versa. This is referred to as the dilution effect. One study showed that foals housed in a mixed (equine-bovine) system excreted half as many strongyle parasite eggs as foals from specialized (equine only) systems[31].

This reduction in parasite load, combined with reasoned deworming practices, helps to reduce the use of dewormers and therefore to limit the development of resistance to dewormers by parasites[32].

However, several factors appear to impact the effectiveness of this dilution effect.

Indeed, in a complementary experimental project, horses excreted the same number of strongyle eggs whether grazing alone or with cattle. In this specific case, the frequency of paddock rotation allowed the grass to regrow between each grazing. The cattle were therefore not forced to graze in areas neglected by the horses, where strongyle larvae, which migrate very little, were concentrated[33].

Moreover, the ratio between the two species may again be a determining factor. Models have shown that in mixed grazing, parasite load decreases in each species in inverse proportion to its share of the overall stocking rate. In other words, the species present in lower numbers in the pasture may benefit the most from this dilution effect[34].

These works therefore illustrate the need for further studies, which would make it possible to define the optimal combination in order to take full advantage of mixed grazing in terms of parasite load.

It should be noted, however, that some bacterial or viral diseases are common to both species, for example brucellosis. In this case, no dilution effect is expected.

Furthermore, mixed grazing with cattle appears to be a risk factor for infection by one of the two blood parasites transmitted via tick bites and responsible for piroplasmosis, Babesia caballi. Since ticks feed on both cattle and horses, mixed grazing increases the number of potential hosts and therefore the risk of infection by the latter.

Increased monitoring during periods of high tick activity (in spring and autumn) is therefore recommended. It should be noted, however, that infections caused by Theileria equi, the second parasite responsible for piroplasmosis, are far more common than those caused by Babesia caballi. Since the transmission pathways of these parasites differ, mixed grazing has not been identified as a risk factor for infections with Theileria equi[35].

As we have just seen, the benefits of horse-cattle grazing are numerous and varied. However, what do we know about the behavioral compatibility between the two species? Do they coexist easily?

On behavior[36]

When sufficient resources and space are available, very few negative interactions occur, and the two species coexist very well. While the most commonly observed behavior is approach (reduction of the distance between individuals of the two species), some animals express stronger affinities with an animal of the other species by, for instance, chasing flies off each other.

Although no injuries were reported during the various research studies, it is recommended that cattle be dehorned to prevent injury to equines. Conversely, increased supervision is required when highly active horses are introduced, encouraging the group to move around more. Excessive locomotor activity in pregnant cows could lead to abortion.

Finally, some breeders find other benefits to this association: the presence of heifers stimulates the curiosity of the horses, providing a form of enrichment while, at the same time the horses, accustomed to being handled, act as mediators and facilitate human interaction with cattle (e.g. tagging).

Conclusion

In conclusion, combining horses and cattle on pasture – by taking advantage of the complementary feeding preferences of these two species – appears to be beneficial in several ways.

Improved use of forage resources and reduced costs associated with pasture maintenance and the purchase of supplementary feed represent an economic advantage for farms[37].

With its positive impact on biodiversity, mixed grazing contributes to agriculture that is more resilient to climate change and also helps to limit the use of dewormers, thus limiting the development of resistance by parasites.

The practice of mixed horse-cattle grazing therefore fits perfectly into the “One Welfare” concept, according to which the welfare of animals, humans and the environment are closely related.

It is important to bear in mind that all the results presented here should be interpreted with caution, as they depend on the chosen type of grazing (continuous or rotational grazing, time spent on paddocks, simultaneous or successive presence of species, stocking rate, ratio, etc.). To fully benefit from the complementarity of these two herbivores and create a balanced ecosystem that benefits both the animals and the plot, further studies are needed to identify the most appropriate grazing management strategies.

In summary

Thanks to Audrey MICHAUD, agricultural engineer, lecturer and researcher in animal sciences, (Clermont Auvergne University, VetAgro Sup, INRAE, UMR Herbivores, Clermont-Ferrand) for her proofreading!

Additional information

Ifce – Webconference « Pâturage mixte équins bovins – Laurie Briot »

Ifce – Brochure « Pâturer à plusieurs espèces pour des bénéfices multiples : Focus sur la mixité équin – bovin »

INRAE – Article « Pâturage mixte bovins-équins, et si les bénéfices étaient multiples ? »

[1] Idele – Les chiffres clés du GEB : Bovins 2023

[3] MASA – Le bien-être et la protection des vaches à viande

[4] Le pâturage des vaches laitières françaises

[5] Agreste – Les exploitations bovines laitières en France métropolitaine en 2020

[6] Ifce – Foncier et filière équine : état des lieux et prospective

[7] Eric Pottier, Audrey A. Michaud, Jean-Pierre J.-P. Farrie, Sylvain Plantureux, René Baumont. Les prairies permanentes françaises au cœur d’enjeux agricoles et environnementaux : des références nouvelles pour une meilleure gestion. Innovations Agronomiques, 2012, 25, pp.85-97. 10.17180/993x-2985. hal-03517814

[8] Equipedia – Ifce : Les graminées

[9] Equipedia – Ifce : Les légumineuses

[10] According to the study by Arrouays et al. (2002), permanent grassland is natural grassland or grassland that has been sown for more than six years and is intended to remain in place; temporary grassland is grassland that has been renewed for less than six years and alternates with crops.

[11] Mauchamp, Leslie, et al. « II. Biodiversité des écosystèmes* prairiaux “. Les prairies : biodiversité et services systémiques, Presses universitaires de Franche-Comté, 2012, https://doi.org/10.4000/books.pufc.12907.

[12] FARRUGGIA A., DUMONT B., JOUVEN M., BAUMONT R., LOISEAU P. (2006) : “La diversité végétale à l’échelle de l’exploitation en fonction du chargement dans un système bovin allaitant du Massif central”, Fourrages, 188, 477-493.

[13] Ilias Karmiris, Panagiotis D. Platis, Savas Kazantzidis, and Thomas G. Papachristou “Diet Selection by Domestic and Wild Herbivore Species in a Coastal Mediterranean Wetland,” Annales Zoologici Fennici 48(4), 233-242, (1 August 2011). https://doi.org/10.5735/086.048.0404

[14] William W. Martin-Rosset, C. Trillaud-Geyl. Pâturage associé des chevaux et des bovins sur des prairies permanentes : premiers résultats expérimentaux. Fourrages, 2011, 207, pp.211-214.

[15] Menard, C., Duncan, P., Fleurance, G., Georges, J.-Y. and Lila, M. (2002), Comparative foraging and nutrition of horses and cattle in European wetlands. Journal of Applied Ecology, 39: 120-133. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2664.2002.00693.x

[16]Adin, G., R. Solomon, M. Nikbachat, A. Zenou, E. Yosef, A. Brosh, A. Shabtay, S. J. Mabjeesh, I. Halachmi, and J. Miron. 2009. Effect of feeding cows in early lactation with diets differing in roughage-neutral detergent fiber content on intake behavior, rumination, and milk production. J. Dairy Sci. 92:3364–3373.

[17] Mambrini, M., Peyraud, J. L., & Rulquin, H. (1988). Comparaison de différentes méthodes de calcul du temps de séjour des résidus alimentaires dans l’ensemble du tube digestif chez la vache laitière. Reproduction Nutrition Développement, 28(Suppl1), 149-150

Carle, B., Dulphy, J. P., L’HOTELIER, L., Moins, G., & Ollier, A. (1980). Comportement alimentaire comparé des ovins et des bovins. Relation avec la digestion des aliments. Reproduction Nutrition Développement, 20(5B), 1633-1639.

[18] Influence des tanins sur la valeur nutritive des aliments des ruminants. N. Zimmer, R.Cordesse. INRA Prod. Anim. 1996, 9 (3), 167-179.

[19] Duncan, P. Time-Budgets of Camargue Horses Ii. Time-Budgets of Adult Horses and Weaned Sub-Adults. Behaviour72, 26–48 (1980). http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/156853980X00023

Boyd, L. E. Time budgets of adult Przewalski horses: Effects of sex, reproductive status and enclosure. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 21, 19–39 (1988). https://doi.org/10.1016/0168-1591(88)90099-8

Boyd, L. E., Carbonaro, D. A. & Houpt, K. A. The 24-hour time budget of Przewalski horses. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci.21, 5–17 (1988). https://doi.org/10.1016/0168-1591(88)90098-6

Kaseda, Y. Seasonal Changes in Time Spent Grazing and Resting of Misaki Horses. Jpn. J. Zootech. Sci., 464–469 (1983). https://doi.org/10.2508/chikusan.54.464

Kiley-Worthington, M. Time-budgets and social interactions in horses: The effect of different environments. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 13, 181–182 (1984)

[20] Duncan P, Foose TJ, Gordon IJ, Gakahu CG, Lloyd M. Comparative nutrient extraction from forages by grazing bovids and equids: a test of the nutritional model of equid/bovid competition and coexistence. Oecologia. 1990 Oct;84(3):411-418. doi: 10.1007/BF00329768. PMID: 28313034.

[21] Stocking rate, or grazing pressure, corresponds to the number of animals present per unit of area.

[22]DUMONT B., FARRUGGIA A., GAREL J.P. Pâturage et biodiversité des prairies permanentes. Renc. Rech. Ruminants, 2007, 14, 17-24.

[23] Fleurance G., Duncan P., Farruggia A., Dumont B., Lecomte T. (2011) : “Impact du pâturage équin sur la diversité floristique et faunistique des milieux pâturés”, Fourrages, 207, 189-199

[24] Benoit Marion. Impact du pâturage sur la structure de la végétation : Interactions biotiques, traits et conséquences fonctionnelles. Université Rennes 1, 2010.

[25] Louise Forteau. Accroître les performances des systèmes d’élevages de chevaux de selle par la mixité avec des bovins allaitants en zones herbagères. Agronomie. Université Clermont Auvergne [2017- 2020], 2019.

[26] The livestock unit (LU) is a reference unit used to aggregate livestock of different species and ages using specific coefficients initially established on the basis of the nutritional or dietary requirements of each type of animal. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Glossary:Livestock_unit_(LSU)/fr

[27] Martin-Rosset W., Trillaud-Geyl C. (2011) : “Pâturage associé des chevaux et des bovins sur des prairies permanentes : premiers résultats expérimentaux”, Fourrages, 207, 211-214.

[28] Nitrophilous plants are plants that live on nitrogen-rich soils and require large amounts of nitrates for their development.

[29] Loucougaray, G., Bonis, A., Bouzillé, J.-B., 2004. Effects of grazing by horses and/or cattle on the diversity of coastal grasslands in western France. Biol. Conserv. 116, 59–71. 0

[30] Ifce – Equipedia « Pâturage mixte équins-bovins, qu’en savons-nous ? »

[31] Forteau L., Dumont B., Sallé G., Bigot G., Fleurance G., 2020. Horses grazing with cattle have reduced strongyle egg count due to the dilution effect and increased reliance on macrocyclic lactones in mixed farms. Animal, 14, 1076-1082.

[32] Ifce – Une vermifugation raisonnée pour limiter les résistances

[33] Fleurance G., Sallé G., Lansade L., Wimel L., Dubois C., Lanore L., Faure S., Dumont B., 2020. La conduite, facteur limitant des attendus du pâturage mixte. In : Journées Sciences et Innovations Équines, FIAP Jean-Monnet, Paris, 17 Novembre 2020.

[34] Hoste H., Guitard J-P., Pons J-C. (2003) « Pâturage mixte entre ovins et bovins : intérêt dans la gestion du parasitisme par les strongles gastro-intestinaux. “. Fourrages, 176, 425-436

[35] Ifce – Equ’Idée. Facteurs de risque d’infestation par les tiques et d’exposition à la piroplasmose équine chez les chevaux de trait en région Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes en France.

[36] Ifce – Equ’Idée, novembre 2017, article 2. Le pâturage mixte bovins–équins : De nouvelles données comportementales à la disposition des éleveurs et détenteurs.

[37] DUMONT, B., COURNUT, S., MOSNIER, C., MUGNIER, S., FLEURANCE, G., BIGOT, G., … RAPEY, H. (2021). Comprendre les atouts de la diversification des systèmes d’élevage herbivores du nord du Massif central. INRAE Productions Animales, 33(3), 173–188.

Keep in mind

- The feed choices of grazing cattle and horses are complementary.

- Mixed grazing can promote: grass utilization, biodiversity of flora and fauna, dilution of parasite load, and human-animal interactions.

- Grazing helps to limit: the purchase of feed, the work involved in maintaining pastures, the administration of dewormers, and antibiotic resistance.

Key Figure

The purchase of fodder in mixed livestock farms.